Tatsuya Nakadai in Masaki Kobayashi’s Harakiri (1962)

OK, obscure enough for you? I admire the character of samurai ronin Tsugumo Hanshirō as played by Tatsuya Nakadai. The man was a force of nature.

Home » Articles posted by Tarnmoor (Page 30)

Tatsuya Nakadai in Masaki Kobayashi’s Harakiri (1962)

OK, obscure enough for you? I admire the character of samurai ronin Tsugumo Hanshirō as played by Tatsuya Nakadai. The man was a force of nature.

I’m just not a pet person. I prefer human friendships and relationships to animals.

Saguaro Cacti in the Arizona Desert

As I prepare for our road trip to Tucson this next week, I have been doing a lot of reading in preparation. It struck me that there are a lot of great books about or set in deserts. Here are an even dozen recommendations organized alphabetically by author:

As I write these, I become acutely aware that there are more titles I should include. Perhaps, as I read more, I will re-visit the subject later.

I would choose track and field, followed by [soccer] football.

Iceland’s Skaftafell Hotel Hard by Svinafell

It was August 2001. I was spending a couple of nights at the Skaftafell Hotel in Svinafell pictured above. While I was eating dinner in the hotel’s restaurant, I was bothered by a rowdy crew of Americans who were yucking it up at a nearby table. When the leader of the crew stepped out to the restroom, the remaining members started talking about him.

Apparently, the missing partyer was none other than Charles H. Keating, Jr., described by Wikipedia as “an American sportsman, lawyer, real estate developer, banker, financier, conservative activist, and convicted felon best known for his role in the savings and loan of the late 1980s.”

When he returned to the table, he saw that I was looking somewhat disgruntled. To make up for the noise his party was making, he invited me to join them and pay for my meal. I respectfully declined, not wanting to associate myself with someone who was a real estate developer, crooked banker, and worse.

The group was traveling around Iceland in a guided minibus tour of the country.

Charles H. Keating, Jr. (1923-2014)

As a saw the white minibus drive away with its noisy contingent, I though back to the one mention of Svinafell in The Njáls Saga. According to Medievalists.Net:

One of the most prominent sexual insults is when Skarpheðin calls Flosi the bride of the troll of Svinafell, this implies that he is used sexually by the troll. This insult is a form of nið, an insult intended to imply that the object is ragr, a passive homosexual or is used in this way by a man, animal or supernatural creature.

Having followed the saga of Lincoln Savings & Loan in the press, I thought he would make a good partner for the Svinafell Troll. Since he is no longer among the living, that is quite possibly what he is doing now.

Community is one of those words I distrust. It has been eroded by being too much in the mouths of politicians.

I have tended to avoid interacting with strangers.

Boats Stranded by the Disappearance of the Aral Sea

In the deserts of Central Asia sits the ghost of the Aral Sea. The original sea bed, shared by Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, is the poster child of decades of neglect. The rivers feeding into the sea were canalized to raise cotton. Very little cotton grows there now. In his Chasing the Sea: Lost Among the Ghosts of Empire in Central Asia, Tom Bissell describes meeting up with a couple of small boys in the eerie desert salt and pesticide-laden atmosphere of a community that used to exist on the shores of the sea.

I sat perched half in and half out of the car. The door was wide open, My chin rested upon the shelf of my hand. The sun was going down, the horizon dyed a Creamsicle orange. I watched a skinny, ravaged-looking dog sniff around various piles of refuse. A dog’s life. Then it occurred to me that American dogs have no idea what a dog’s life is. Suddenly, two little boys appeared from behind one of the houses and approached me. They were brothers, clearly. One was taller and certainly older. The other was small, perhaps five years old. The boy’s head was pumpkin-sized, seemingly twice the circumference of his brother’s, who was regarding me coldly. The younger boy smiled, his teeth cavitied and yellow, his skinny body completely naked and covered in dust. The dust was spread so evenly over his body it seemed deliberately applied. His uncircumcized penis looked like a tiny anteater nose. I smiled back at him. “Ismingiz nimah?” I asked. What is your name?

Before the boy could answer, his older brother inexplicably struck him from behind. The boy flopped face-first in the dust. The shove was two-handed and savage, like something out of provincial hockey. A sound, perhaps “Hey—,” filled my mouth. But I did nothing. The younger brother coughed into the dust. He had landed badly, arms at his sides. Now he tried to get to his feet. His brother placed a foot on his naked bottom and, almost tenderly, pushed him back into the dirt. He stared down, having satisfied some obscure but insatiable impulse, and then walked away. I waited for tears, the shrieks and cries of fraternal terror. But no. Nothing at all. The naked dusty child was silent. The dog trotted over and, as the boy picked himself up, he searched the ground blindly with a small pawing hand. Finally, he stood holding a triangular rock. He turned and threw it at the dog, hitting the creature full in the ribs; the dog flinched but otherwise took the blow in silence. The younger boy simply walked away. I made soft kissing sounds to summon the dog. It was understandably skittish, but I persisted. I did not know what else to do. When it slunk over, head lowered and panting, I saw a red spiderlike creature dug into its collarless neck. I extended my hand. The dog bit me and staggered off.

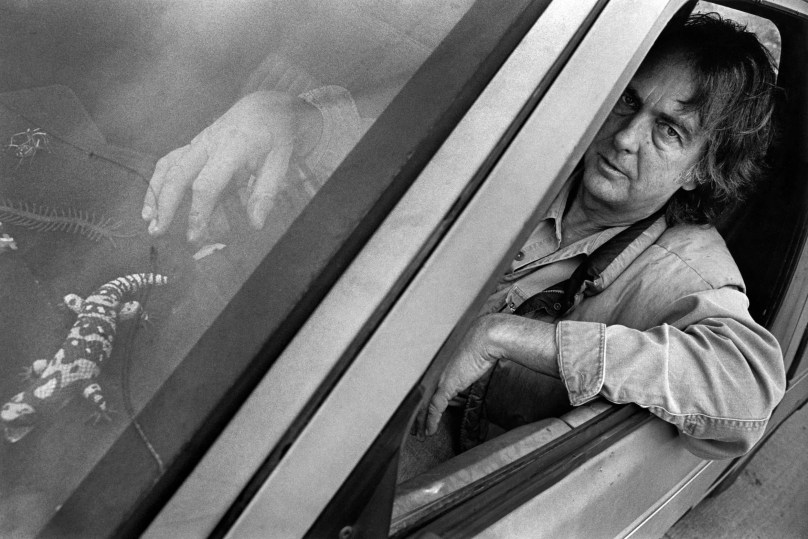

Arizona Writer Charles Bowden (1945-2014)

Typically, the only books I read during the month of January are by authors I have not before encountered. I call this my Januarius project. This last January, however, I was too ill to read more than two books—and that at the end of the month. So I decided to hold this year’s Januarius in March.

During this month, I read fifteen books by authors who were new to me:

All in all, it was a good month with some writers I would like to revisit—particularly Charles Bowden. Next week, Martine and I are going to Tucson, Bowden’s home turf, where I plan to read some more of his work.

I would much rather see something named after someone that matters or has mattered to me. Once I’m gone, I will be past caring for something named after me; but while I’m alive, it would warm my heart to commemorate my love for my mother, father, brother, or Martine.

You must be logged in to post a comment.