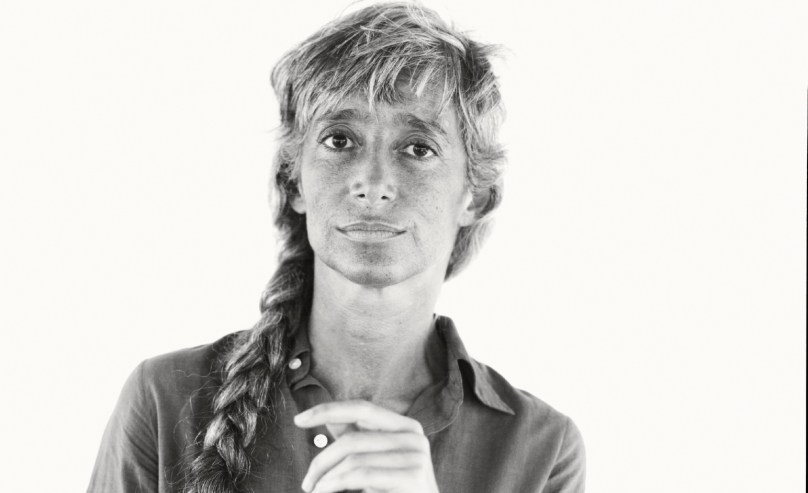

Storm Off the Island of Hoy, Orkney, Scotland

For many years, Scottish writer and poet George Mackay Brown wrote a column for the local newspaper of the Orkney Islands, The Orcadian. The following column from his collection Rockpools and Daffodils: An Orcadian Diary 1979-1991. describes a once-in-a-generation thunderstorm:

I think we have never had a thunderstorm like it this generation in Orkney.

We had almost forgotten what a thunderstorm was. A few warnings lingered in the memory. ‘Cover the mirrors’ … ‘Don’t take shelter under a tree’ … Someone had said to us as children, ‘The lightning won’t strike if you wear rubber boots.’ … (Old wives’ mutterings beside the fire, half-forgotten.)

I suppose we ought to have been prepared for thunder—day after day of sunshine, a still brooding loaded atmosphere, no rain for weeks.

We were so thankful for early tokens of a good summer, no-one was complaining.

It came with dramatic suddenness, between breakfast and lunch. The darkening sky, the first vfew rain-drops heavy as coins, a low growl across the sky (as if Thor wasn’t in the sweetest of tempers). But Thor, in the last two or three decades, has occasionally given a growl or two on a summer day, and turned over to sleep again.

Thor the Thunderer had urgent things to do today, it soon became obvious. He had business on his hands. His mighty hammer thudded on the hills, amid flashings.

The clouds were torn apart. Black bags of water, they emptied themselves upon the town. The gardens, at least, must have loved it, after the long drought. One could sense the roots gorging themselves.

The stones of Stromness [Brown’s home town] could do nothing with the sudden weight of water. The gutters gushed and spluttered. Down the Distillery close came a river of water, and swung south. The lightning was mostly vivid blinks, followed at once by peal upon peal. Hundreds of tons of coal were being shifted along the horizon. There was a mighty furniture removal in the sky: grand pianos and huge Victorian sideboards. And sometimes it was as if a cannon had exploded by accident in a close or down a pier, a hideous ripping of hot metal.

The cosmic electricity had quelled the little expensive electricity that man makes. I switched on the light in the eerie darkling room—nothing doing.

A candle responded with a tranquil flame.

A golden fork stabbed down and singed Hoy Sound!

After a time it seemed that Thor had finished his mighty labours for the day. The sky brightened, the thunder grumbled under the horizon.

But Thor must have forgotten some tool in his sky-smithy. Back he came and blew up his forge and struck the anvil a few more mighty blows: while we nervous earthlings below trembled. By early afternoon it was all over. We looked at each other in the cleansed air, we spoke to each other, like folk who had had some wonderful, frightening new experience.

You must be logged in to post a comment.