The author of everybody’s favorite book, To Kill a Mockingbird (1960), died today at the age of 89. Most literate Americans revere her memory, even after the recent publication of Go Set a Watchman (2015), in which Atticus Finch is revealed to be a (gasp!) bigot. I take no position on it, however, as I have not read the book; and I find the first reaction to anything by the media is usually wrong.

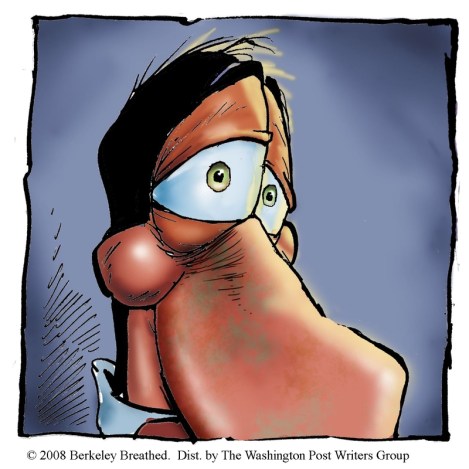

But what I want to write about is a letter Ms. Lee wrote to cartoonist Berkeley Breathed twenty years ago, when he decided to voluntarily stop publishing “Bloom County,” “Outland,” and “Opus.” It was the character of Opus the Penguin that she would miss the most. Here is the text of the letter as it appeared in Breathed’s Facebook posting today:

Dear Mr. Breathed,

This is a plea from a dotty old lady, and from others not dotty at all: Please don’t shut down OPUS. Can’t you at least give him a reprieve? OPUS is simply the best comic strip there is….

The letter goes on, but that’s all that Breathed shares with us. Fortunately, Opus is back, along with his Bloom County buddies, on Facebook, where I religiously check it each day.

Commenting on her letter, the cartoonist writes:

Bloomers: Many, but not all of you, know that in the way that creative life can often surprise, Harper Lee was one of you. One of us. You might be as surprised as I am that she played a large role in my recent return to the streets of Bloom County—streets inspired by those of Maycomb. When I retired Opus from the Sunday comics some years ago, Harper let me know her displeasure, with all the southern, gracious elegance we knew her for. See the letter below. I’ve waited until her passing to show it. We came to exchange many similar notes… including one in which she grudgingly forgives me for my retirement (irony alert). Imagine my 14 year-old self—freshly savoring the first reading of Mockingbird and sending Miss Lee a fan letter in 1970—being told about another fan letter returning my way almost 40 years distant. Life is wonderful and strange and wistful and happy at the same time. And I’m happy to share this with all of you today.

To follow Opus and his buddies, click here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.