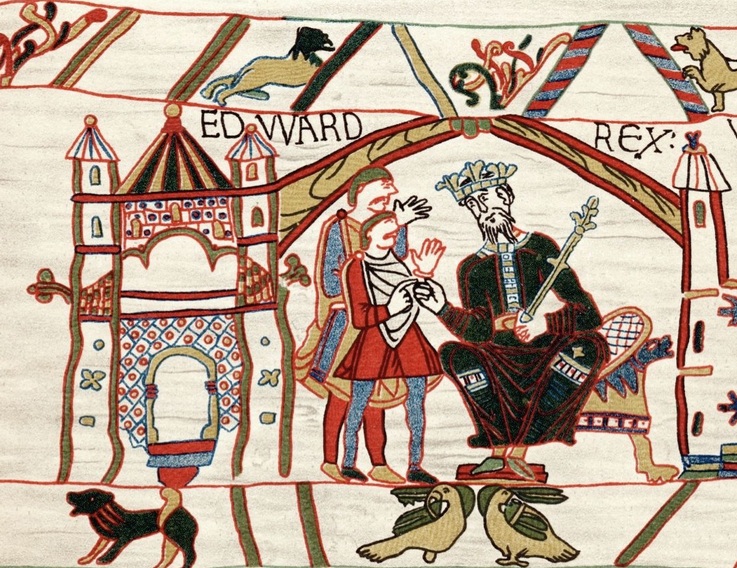

One of Many Anglo-Saxon Edwards Who Preceded the Conquest

The English language has a long history. We don’t have any samples of what the English spoke during the Roman occupation. In fact, it was not until the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes crossed the Channel into Britain that we have the bare bones of a literature. Today, I present one of the great Anglo-Saxon poems.

If you want to hear the poem in the original Anglo-Saxon of the Dark Ages, you can do so by checking out this YouTube site. It is a far, far cry from the language we speak today.

Here is “The Wanderer” in a modern translation from the Poetry Foundation:

The Wanderer

Always the one alone longs for mercy,

the Maker’s mildness, though, troubled in mind,

across the ocean-ways he has long been forced

co stir with his hands the frost-cold sea,

and walk in exile’s paths. Wyrd is fully fixed.

Thus spoke the Wanderer, mindful of troubles,

of cruel slaughters and dear kinsmen’s downfall:

“Often alone, in the first light of dawn,

I have sung my lament. There is none living

to whom I would dare to reveal clearly

my heart’s thoughts. I know it is true

that it is a nobleman’s lordly nature

to closely bind his spirit’s coffer,

hold fast his treasure-hoard, whatever he may think.

The weary mind cannot withstand wyrd,

the troubled heart can offer no help,

and so those eager for fame often bind fast

in their breast-coffers a sorrowing soul,

just as I have had to take my own heart—

Often wretched, cut off from my own homeland,

far from dear kinsmen—and bind it in fetters,

ever since long ago I hid my gold-giving friend

in the darkness of earth, and went wretched,

winter-sad, over the ice-locked waves,

sought, hall-sick, a treasure-giver,

wherever I might find, far or near,

someone in a meadhall who might know my people,

or who would want to comfort me, friendless,

accustom me to joy. He who has come to know

how cruel a companion is sorrow

for one with few dear friends, will understand:

the path of exile claims him, not patterned gold,

a winter-bound spirit, not the wealth of earth.

He remembers hall-holders and treasure-taking,

how in his youth his gold-giving lord

accustomed him to the feast—that joy has all faded.

And so he who has long been forced to forego

his lord’s beloved words of counsel will understand:

when sorrow and sleep both together

often bind up the wretched exile,

it seems in his mind that he clasps and kisses

his lord of men, and on his knee lays

hands and head, as he sometimes long ago

in earlier days enjoyed the gift-throne.

But when the friendless man awakens again

and sees before him the fallow waves,

seabirds bathing, spreading their feathers,

frost falling and snow, mingled with hail,

then the heart’s wounds are that much heavier,

longing for his loved one. Sorrow is renewed

when the memory of kinsmen flies through the mind;

he greets them with great joy, greedily surveys

hall-companions—they always swim away;

the floating spirits bring too few

familiar voices. Cares are renewed

for one who must send, over and over,

a weary heart across the binding waves.

And so I cannot imagine for all this world

why my spirit should not grow dark

when I think through all this life of men,

how suddenly they gave up the hall-floor,

mighty young retainers. Thus this middle-earth

droops and decays every single day;

and so a man cannot become wise, before he has weathered

his share of winters in this world. A wise man must be patient,

neither too hot-hearted nor too hasty with words,

nor too weak in war nor too unwise in thoughts,

neither fretting nor fawning nor greedy for wealth,

never eager for boasting before he truly understands;

a man must wait, when he makes a boast,

until the brave spirit understands truly

where the thoughts of his heart will turn.

The wise man must realize how ghastly it will be

when all the wealth of this world stands waste,

as now here and there throughout this middle-earth

walls stand blasted by wind,

beaten by frost, the buildings crumbling.

The wine halls topple, their rulers lie

deprived of all joys; the proud old troops

all fell by the wall. War carried off some,

sent them on the way, one a bird carried off

over the high seas, one the gray wolf

shared with death—and one a sad-faced man

covered in an earthen grave. The Creator

of men thus destroyed this walled city,

until the old works of giants stood empty,

without the sounds of their former citizens.

He who deeply considers, with wise thoughts,

this foundation and this dark life,

old in spirit, often remembers

so many ancient slaughters, and says these words:

‘Where has the horse gone? where is the rider? where is the giver of gold?

Where are the seats of the feast? where are the joys of the hall?

O the bright cup! O the brave warrior!

O the glory of princes! How the time passed away,

slipped into nightfall as if it had never been!

There still stands in the path of the dear warriors

a wall wondrously high, with serpentine stains.

A storm of spears took away the warriors,

bloodthirsty weapons, wyrd the mighty,

and storms batter these stone walls,

frost falling binds up the earth,

the howl of winter, when blackness comes,

night’s shadow looms, sends down from the north

harsh hailstones in hatred of men.

All is toilsome in the earthly kingdom,

the working of wyrd changes the world under heaven.

Here wealth is fleeting, here friends are fleeting,

here man is fleeting, here woman is fleeting,

all the framework of this earth will stand empty.’

So said the wise one in his mind, sitting apart in meditation.

He is good who keeps his word, and the man who never too quickly

shows the anger in his breast, unless he already knows the remedy

a noble man can bravely bring about. It will be well for one who seeks mercy,

consolation from the Father in heaven, where for us all stability stands.

A Word of Explanation

The following discussion is taken from the Octavia Randolph website:

Wyrd is an Old English noun, a feminine one, from the verb weorthan “to become”. It is related to the Old Saxon wurd, Old High German wurt, Old Norse urür. Wyrd is the ancestor of the more modern weird, which before it meant odd or unusual in the pejorative sense carried connotations of the supernatural, as in Shakespeare’s weird sisters, the trio of witches in MacBeth. The original Wyrd Sisters were of course, the three Norns, the Norse Goddesses of destiny.

Wyrd is Fate or Destiny, but not the “inexorable fate” of the ancient Greeks. “A happening, event, or occurrence”, found deeper in the Oxford English Dictionary listing is closer to the way our Anglo-Saxon and Norse forbears considered this term. In other words, Wyrd is not an end-point, but something continually happening around us at all times. One of the phrases used to describe this difficult term is “that which happens”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.