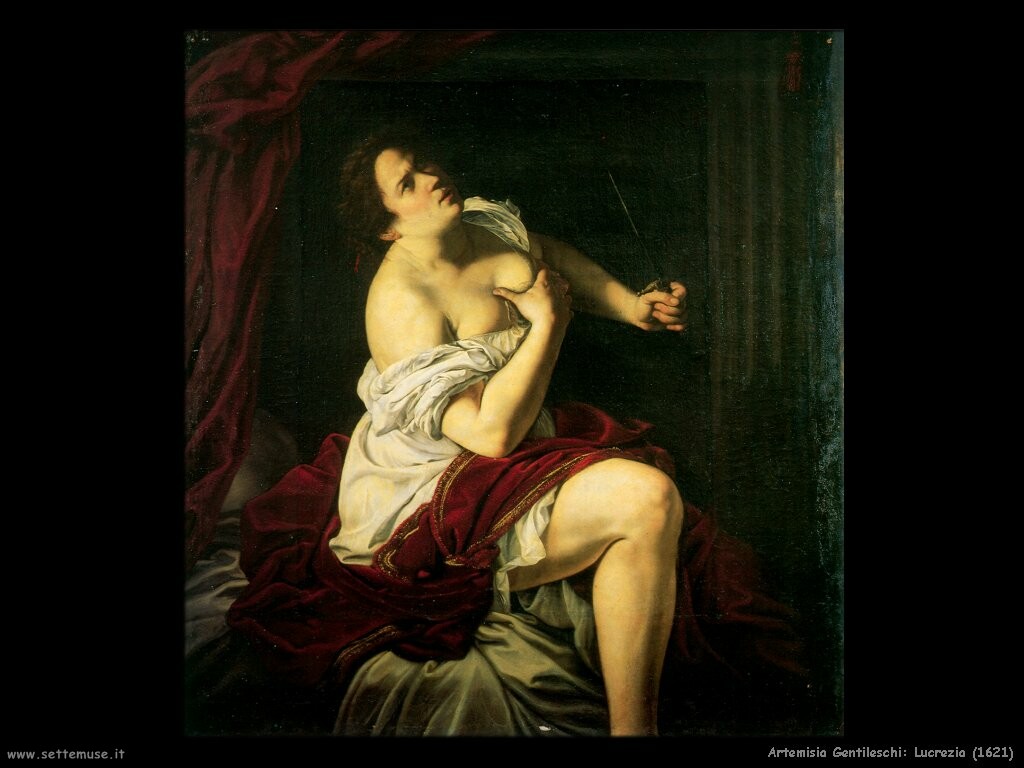

“The Triumph of Galatea” by Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1656)

During Women’s History Month in 2024, I would like to honor several women whom I think have made a substantial contribution to our civilization. All of them lived in a time when the very thought of a woman’s contribution in anything other than childbirth, the domestic arts, or copulation was considered to be revolutionary.

The name of Galatea is not mentioned much today, but remember that it is coupled with the name of Pygmalion. Galatea was the statue of a lovely nymph that came to life when the sculptor fell in love with the image he created. It was that tale that led to George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion and, later still, to the musical My Fair Lady.

Artemisia Gentileschi was a noted artist in her own lifetime. According to Wikipedia, “For many years Gentileschi was regarded as a curiosity, but her life and art have been reexamined by scholars in the 20th and 21st centuries, with the recognition of her talents exemplified by major exhibitions at internationally esteemed fine art institutions, such as the National Gallery in London.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.