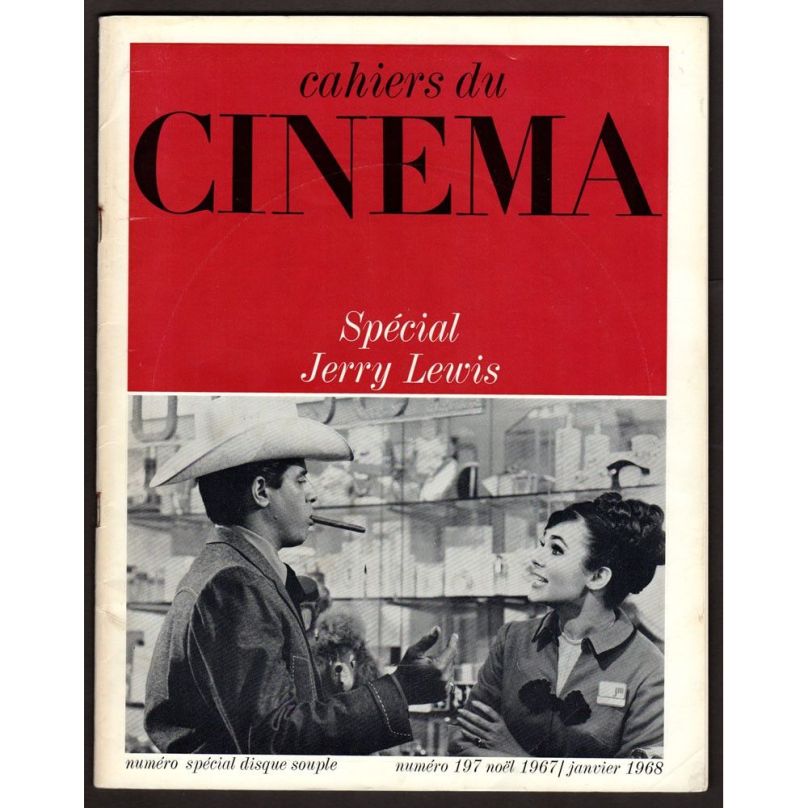

This Is the Magazine That Started It All

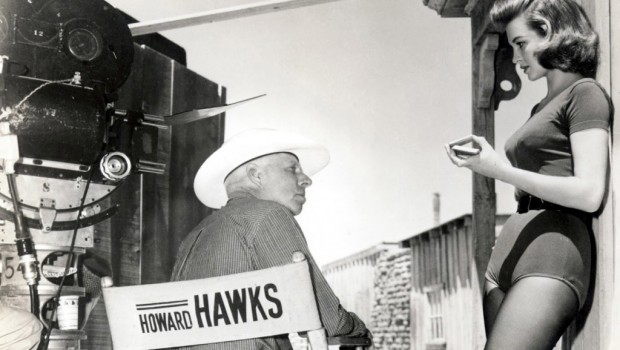

The Politique des Auteurs started in France with the writers of Cahiers du Cinema. André Bazin and a young cadre of rising filmmakers and critics felt that the French cinema was becoming too literary and that much was to be learned from the vitality of the American film industry. With almost every issue, they were discovering scores of new film artists such as John Ford, Howard Hawks, Nicholas Ray, and even such downmarket geniuses as Edgar G. Ulmer.

By 1962, the auteurists found an American disciple in Andrew Sarris, film critic for The Village Voice in New York. For the Winter 1962-1963 issue of Film Culture, Sarris created a whole issue dedicated to the auteur theory. As a student at Dartmouth College, I paid to photocopy the entire issue and used it religiously as a guide until Sarris came out a few years later with the greatly expanded American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929-1968.

The Notorious Auteur Issue of 1962-1963

Circles and Squares: In the interim, Pauline Kael published a blistering attack in Film Quarterly called “Circles and Squares: Joys and Sarris.” Many of her attacks hit home, and they certainly exposed Sarris’s weaknesses as a film theoretician. I had met Pauline Kael and liked her work, but as a young man I was a budding auteurist.

Now, half a century and thousands of films later, I still see myself as having been influenced by the Cahiers crowd and Sarris, but I think there is a lot more to film than an a priori theory imposed from above. On the plus side, the auteurists opened me to the incredible riches of the American film—but I started liking films by such card-carrying non-auteurs as Felix Feist, Edward L. Cahn, Robert Florey, and Charles Vidor.

I give the credit to the auteur theory for introducing me to the idea that American films can also be great. I started my love of film by watching such foreign productions as Carl Dreyer’s Day of Wrath (1948) and Wojciech Has’s The Saragossa Manuscript (1962); but by the late 1960s I was beginning to give Hollywood its due and loosened up considerably.

You must be logged in to post a comment.