Detail of Tingatinga Image from Tanzania

On Thursday of last week, I spent several hours at the Fowler Museum at UCLA viewing art that is outside the normal art marketplace. According to their website:

The Fowler Museum at UCLA explores global arts and cultures with an emphasis on Africa, Asia, the Pacific, and the Indigenous Americas—past and present. The Fowler enhances understanding and appreciation of the diverse peoples, cultures, and religions of the world through dynamic exhibitions, publications, and public programs, informed by interdisciplinary approaches and the perspectives of the cultures represented. Also featured is the work of international contemporary artists presented within the complex frameworks of politics, culture and social action. The Fowler provides exciting, informative and thought-provoking exhibitions and events for the UCLA community and the people of greater Los Angeles and beyond.

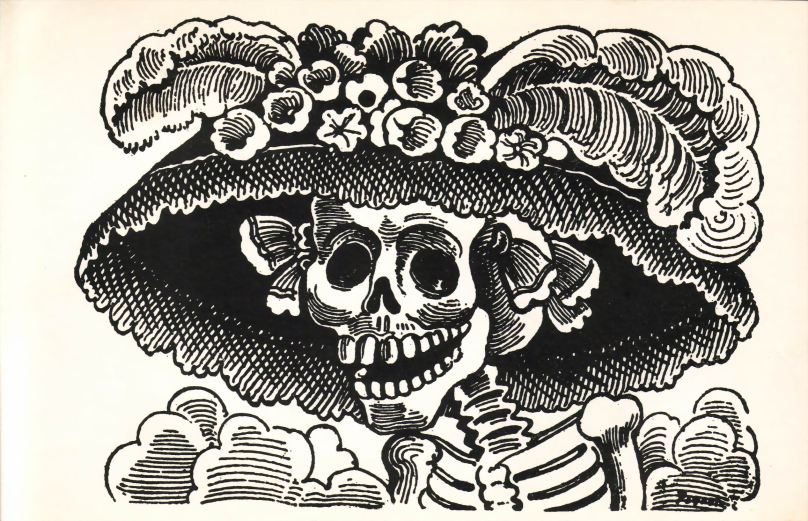

One gallery presented the work of Amir H. Fallah, a Persian-American, in an exhibit entitled “The Fallacy of Borders.” Then there were a number of Jain embroidered hangings from Indian shrines. There were a few Tanzanian paintings from the Tingatinga school left over from a larger exhibit that closed last month. Finally, there was the ongoing exhibit entitled “Intersections: World Arts, Local Lives” which included the following sculpture group from Mexico:

Calavera Sculpture from Mexico

Most of this art was not created for corporate conference rooms or major art museums. Much of it is folk art created to reflect a local culture. Some of it is commercial, but never for the art market of New York or London. All of it is outside European-American culture (except for some aboriginal American art).

When I visit the Fowler or other folk art museums, such as the Museo Mindalae in Quito, Ecuador, I see art that opens up other cultures to me. I am not just seeing another stale work of abstract expressionism created to make money in the New York market. I am seeing something that speaks for a people or for a religion. The result is utterly refreshing.

I hope in the weeks to come to reprise some of the folk art I have seen on my travels.

You must be logged in to post a comment.