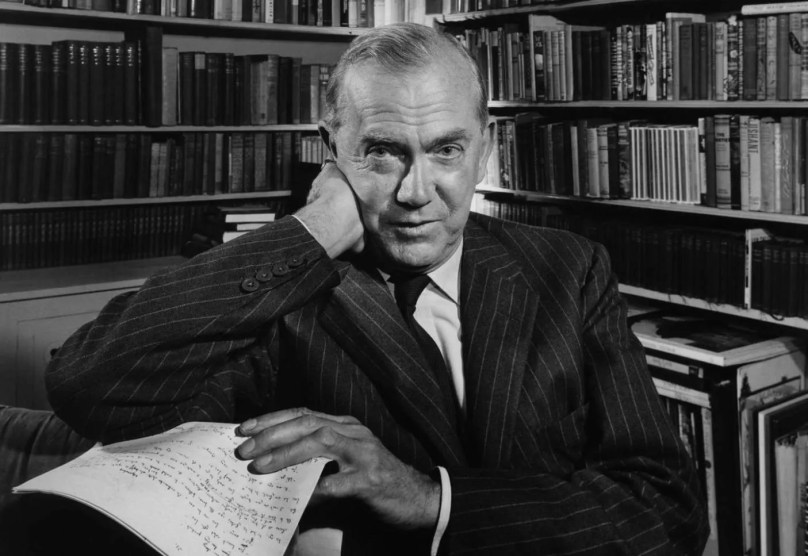

British Writer Graham Greene (1904-1991)

In the 1920s and 1930s, Mexico suddenly came to the attention of the English. There had been a messy revolution, numerous political assassinations, persecution of the Catholic Church, and the nationalization of the country’s petroleum assets. English writers seemed to want to understand Mexico, even if it meant an investment of several weeks to do so.

The results were pretty much a hodge-podge. Probably the most interesting works were by Graham Greene in his novel The Power and the Glory (1940) about the religious persecution in Tabasco and Chiapas and The Lawless Roads (1939), a travel book in which the author admits to loathing Mexico. “No hope anywhere. I have never been in a country where you are more aware all the time of hate,” this after he broke his glasses while on the road.

Also interesting is Aldous Huxley (1894-1963) with his tour of Mexico and Central America published in 1934 called Beyond the Mexique Bay.

D. H. Lawrence was hot and cold on the subject of Mexico. His Mornings in Mexico (1927) shows that he knew how to appreciate Mexico, whereas The Plumed Serpent (1926) is a weird and unconvincing novel.

Worst of the books was Evelyn Waugh’s Robbery Under Law: The Mexican Object-Lesson (1939), in which it is apparent that he is in a permanent snit on the subject of Mexico, and his sources were all obviously fascistic jackals. I read the first half of the book with its endless complaints of Lazaro Cardenas’s nationalization of the petroleum industry (was he possibly a disappointed investor?) and the United States’s hamfisted interventions during the Mexican Revolution. At no point did I feel that Waugh was seeing with his own eyes. (And yet, he was such a brilliant novelist. Go figure!)

You must be logged in to post a comment.