November 2 in the Catholic liturgy is All Souls’ Day, or in Mexico, El Dia de Los Muertos, the Day of the Dead. Here is a poem by Alberto Rios, a Hispanic resident of Arizona.

November 2: Día de los muertos

1

It is not simply the Day of the Dead—loud, and parties.

More quietly, it is the day of my dead. The day of your dead.

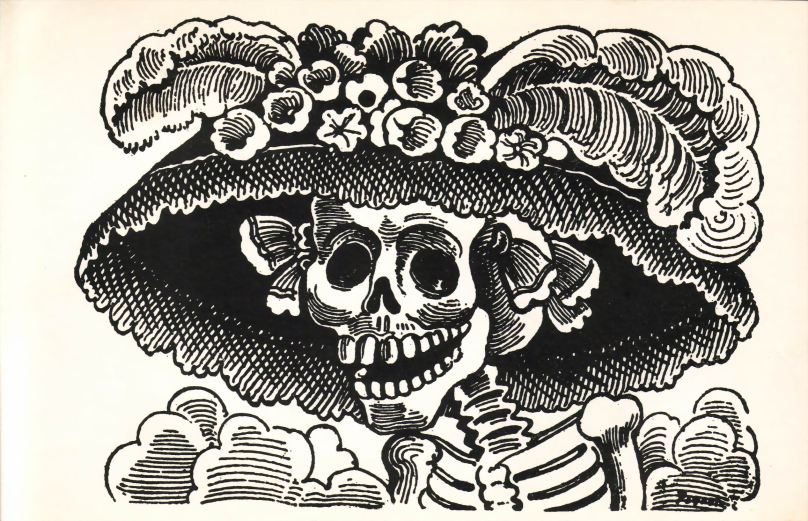

These days, the neon of it all, the big-teeth, laughing skulls,

The posed calacas and Catrinas and happy dead people doing funny things—

It’s all in good humor, and sometimes I can’t help myself: I laugh out loud, too.

But I miss my father. My grandmother has been gone

Almost so long I can’t grab hold of her voice with my ears anymore,

Not easily. My mother-in-law, she’s still here, still in things packed

In boxes, her laughter on videotape, and in conversations.

Our dog died several years ago and I try to say his name

Whenever I leave the house—You take care of this house now,

I say to him, the way I always have, the way he knows.

I grew up with the trips to the cemetery and pan de muerto,

The prayers and the favorite foods, the carne asada, the beer.

But that was in the small town where my memory still lives.

Today, I’m in the big city, and that small town feels far away.

2

The Day of the Dead—it’s really the days of the dead. All Saints’ Day,

The first of November, also called the día de los angelitos—

Everybody thinks it’s Day of the Dead—but it’s not, not exactly.

This first day is for those who have died a saint

And for the small innocents—the criaturas—the tender creatures

Who have been taken from us all, sometimes without a name.

To die a saint deserves its day, to die a child. The following day,

The second of November, this is for everybody else who has died

And there are so many,

A grandmother, a father, a distant uncle or lost cousin.

It is hard enough to keep track even within one’s own family.

But the day belongs to everyone, so many home altars,

So many parents gone, so many husbands, so many

Aunt Normas, so many Connies and Matildes. Countless friends.

Still, by the end of the day, we all ask ourselves the same thing:

Isn’t this all over yet?

3

All these dead coming after—and so close to—Halloween,

The days all start to blend,

The goblins and princesses of the miniature world

Not so different from the ways in which we imagine

Those who are gone, their memories smaller, their clothes brighter.

We want to feed them only candy, too—so much candy

That our own mouths will get hypnotized by the sweetness,

Our own eyes dazzled by the color, our noses by the smells

The first cool breath of fall makes, a fire always burning

Somewhere out there. We feed our memories

And then, humans that we are, we just want to move quickly away

From it all, happy for the richness of everything

If unsettled by the cut pumpkins and gourds,

The howling decorations. The marigolds—cempasúchiles—

If it rains, they stink, these fussy flowers of the dead.

Bread of the dead, day of the dead—it’s hard to keep saying the word.

4

The dead:

They take over the town like beach vacationers, returning tourists getting into everything:

I had my honeymoon here, they say, and are always full of contagious nostalgia.

But it’s all right. They go away, after a while.

They go, and you miss them all over again.

The papel picado, the cut blue and red and green paper decorations,

The empanadas and coconut candy, the boxes of cajeta, saladitos,

Which make your tongue white like a ghost’s—

You miss all of it soon enough,

Pictures of people smiling, news stories, all the fiestas, all this exhaustion.

The coming night, the sweet breads, the bone tiredness of too much—

Loud noise, loud colors, loud food, mariachis, even just talking.

It’s all a lot of noise, but it belongs here. The loud is to help us not think,

To make us confuse the day and our feelings with happiness.

Because, you know, if we do think about our dead,

Wherever they are, we’ll get sad, and begin to look across at each other.

You must be logged in to post a comment.