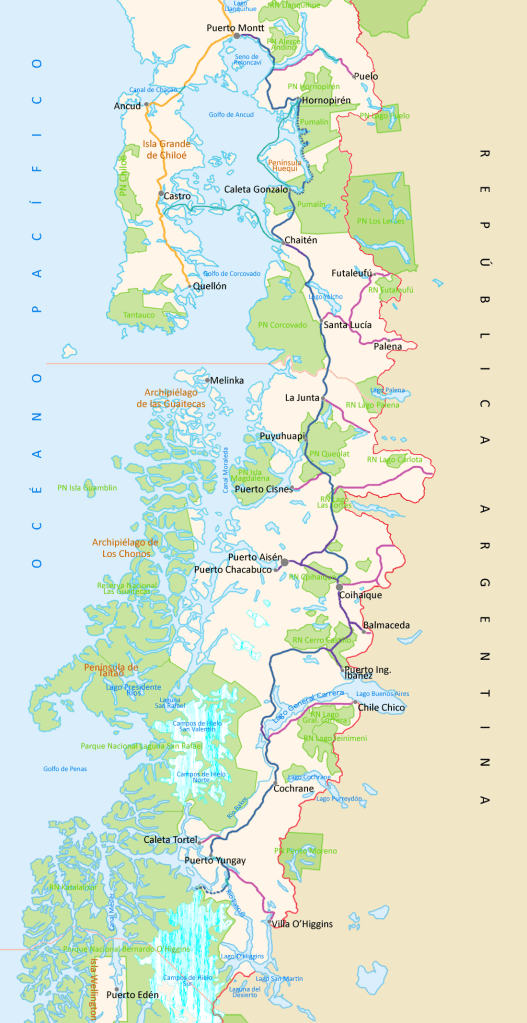

The Other Great North/South Road in South America

Like the Chile’s Carretera Austral, Argentina’s Ruta Cuarenta (Route 40) is another of the great South American highways. It runs for 3,246 miles (5,224 km) from the northern tip of Argentina where it meets the altiplano of Bolivia all the way to Cabo Virgenes, the most southerly point on the South American mainland. It doesn’t include Tierra del Fuego which is on an island.

Although I have never been on the Carretera Austral, I have ridden Ruta 40 between Neuquén and San Carlos Bariloche in 1995. Both highways are practically up against the Andes. Where Coyhaique is the only large town on the Chilean highway, Ruta 40 goes through Cafayate, Mendoza, San Carlos Bariloche, Esquel, Rio Turbio, and Rio Gallegos on its way to the large Magellanic Penguin sanctuary by Cabo Virgenes. To go further south in Argentina, one has to take a Chilean ferry across the Straits of Magellan before crossing over to Ruta 3 to Rio Grande and Ushuaia.

There are stretches of the highway south of Rio Negro Province that are not yet paved, being the windy deserts of Patagonia. Even so, a good part of the southern highway is the only land route from Chile’s Villa O’Higgins to Puerto Natales. In addition, there are Argentinian buses plying the route

I would love to take Ruta 40 along its entire length, but I would require an SUV, at least two spare tires, and an auto mechanic. Oh, and for certain areas, a guide. Alas, I am too old and poor to be able to indulge in this travel dream of mine.

You must be logged in to post a comment.