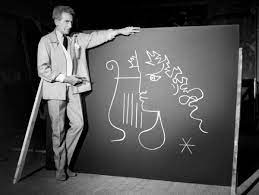

Jean Marais as the Beast and Josette Day as Beauty

Today was probably the tenth or fifteenth time I have ever viewed Jean Cocteau’s La belle et la bête (1946). Each time, I was enthralled by the magic; and, today, for the first time I introduced Martine to the film, fearing that she wouldn’t like it. She loved it! So much so that she asked about Cocteau’s other films.

The version Cocteau used was written by Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont and published in 1757 along with other fairy tales. Cocteau seems to have set the story in the 17th century. Riding horseback to town through the forest to inquire about his merchant ships, which were overdue in port. On his way back, he stops at a magical castle, from whose gardens he cuts a rose to give to his daughter Belle. At once, he is confronted by the beast, who demands either his life or that of one of his daughters.

Here the story seems almost to merge with the Cinderella fairy tale, in that Belle’s two sisters are vain and selfish. But Belle returns (via a magic horse called La Magnifique) to the Beast’s castle. The Beast falls for her and tells her that he requests to have dinner with him once a day at seven o’clock, whereupon he would ask if she would become his wife.

In the end, she falls for the Beast. Once she pledges her troth to him, he is transformed into a resplendent prince who flies away with her through the air.

The strength of the film is Cocteau’s devotion to the magic of the story. In the film prologue, he writes:

Children believe what we tell them. They have complete faith in us. They believe that a rose plucked from a garden can bring drama to a family. They believe that the hands of a human beast will smoke when he kills a victim, and that this beast will be shamed when confronted by a young girl. They believe in a thousand other simple things. I ask of you a little of this childlike simplicity, and to bring us luck, let me speak four truly magic words, Childhood’s Open Sesame: “Once upon a time…”

Over the last fifty-odd years, this film has become a perennial favorite of mine. The nobility of Jean Marais in the role of the Beast and the loveliness of Josette Day as Belle have become hard-wired in my brain.

I highly recommend seeing this film either on the big screen or the Criterion DVD version (which I saw today). It is one of the evergreen masterpieces of the cinema.

34.052234

-118.243685

You must be logged in to post a comment.