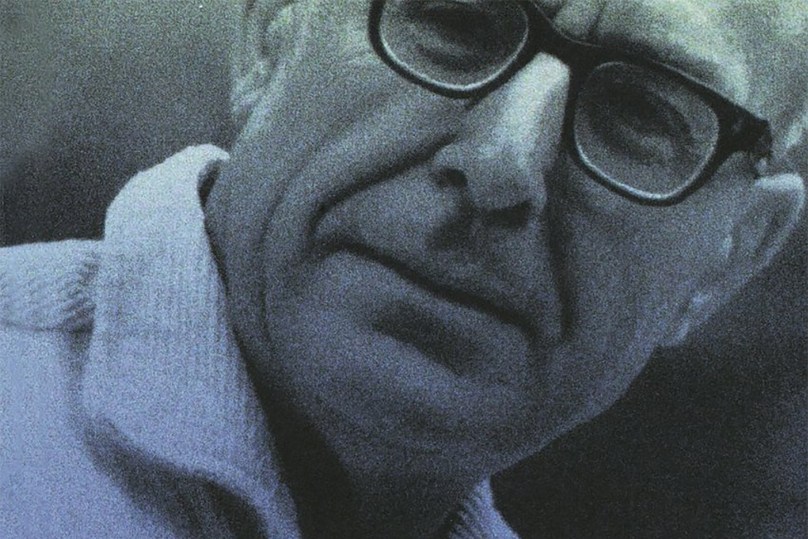

Yesterday, I posted a quote from Loren Eiseley’s The Unexpected Universe about spiders. He frequently thought about and wrote about seemingly small and insignificant creatures. Here is a poem he wrote about spiders in 1928 that was published in Prairie Schooner:

Spiders

Spiders

are poisonous, hairy, secretive.

Spiders are old—

they watch from dark corners while wills are made.

They weave grey webs for flies, and wait…

tiles drop from the roof,

leaves turn moldy under the black, slanting rain,

people die…

and the spiders inherit everything.

Spiders are antiquarians—

fond of living among ghosts and haunted ruins,

The black jade pillars totter in the halls of Marduk;

stones fall from the archways,

at night grey sand

whines by the lampless windows.

The god lies shattered,

his green-jeweled eyes are gone;

the sockets are hacked and empty as a skull.

Upon his face a squat tarantula is creeping…

a bland yellow noon

smiles at a black tarantula

creeping on the skull of a god!

Spiders are ghouls—

they live secret lives in graveyards,

A red spear of light

pierces the stained vault-window

and makes a warm pool on a black coffin in a niche.

A lean spider droops on a thread from above,

falls into the light, and changes color…

a crimson spider

sprawling on an ebony coffin

mumbles a fly in his toothless mouth.

Spiders…

time is a spider,

the world is a fly

caught in the invisible, stranded web of space.

It sways and turns aimlessly

in the winds blowing up from the void.

Slowly it desiccates… crumbles…

the stars weave over it.

It hangs…

forgotten.

You must be logged in to post a comment.