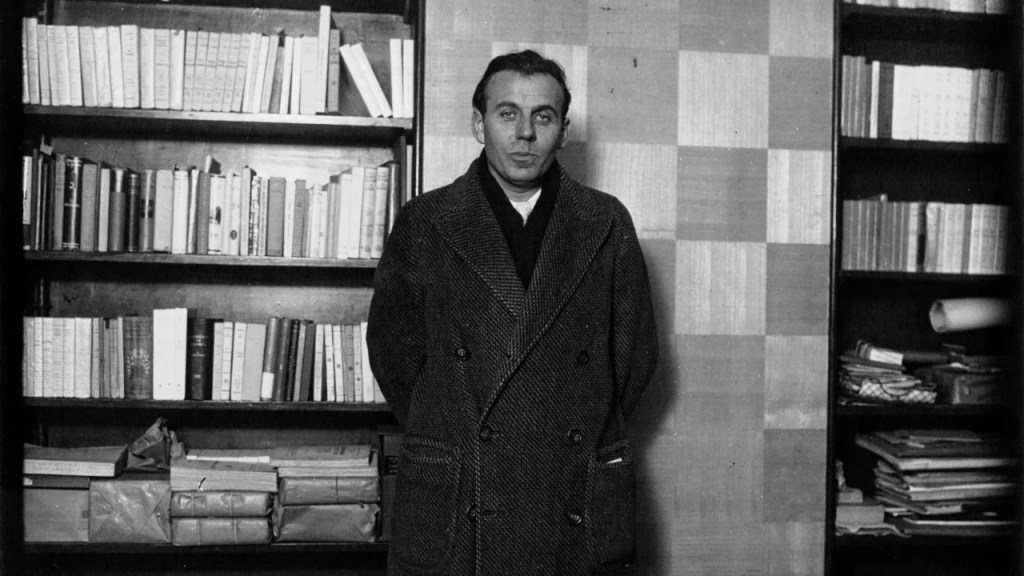

Doctor Destouches (aka Louis-Ferdinand Céline)

He will never win any humanitarian awards, or, for that matter, any awards, but Louis-Ferdinand Céline is one of the greatest writers of the twentieth century, an anti-Semite, a Nazi sympathizer, and probably a very decent human being otherwise. Born Louis Ferdinand Auguste Destouches in Courbevoix, France in 1894, Céline became a wounded war hero at Ypres in 1914

After the war, he became a physician and toured Africa and the Americas working for the League of Nations. In 1932, he published his greatest and most approachable novel, Journey to the End of the Night (Voyage au bout de la nuit). Unfortunately, in the early 1940s, he published several anti-Semitic books urging closer ties to Hitler’s Germany.

After the Allied invasion of France, Céline fled to Germany after having been identified by the Resistance and the British as a collaborationist. It was the beginning of a long and confused period escaping Allied bombing attacks and the Russian Army that was brilliantly described in his trilogy about being a guest of the Nazis as they were being pounded to pieces:

- Castle to Castle (D’un château l’autre) 1957

- North (Nord) 1960

- Rigadoon (Rigadon) 1961

Years after reading the first two volumes, I have just finished reading Rigadoon and loving it. Céline and his wife are constantly being shuttled on trains from one bombed-out city to another. At one point, he escorts a group of eighteen severely retarded children from Hannover to Hamburg and manages to transfer them to a special Swedish Red Cross train taking them to safety. Unfortunately, the same train took Céline to Copenhagen, where he served a year in prison for his collaboration with the Nazis.

He died in 1961. Although his novels were a powerful influence on other novelists, Céline was never treated with the honor that his literary and medical work deserved. He spent his last years being a doctor treating poor patients in the slums of Paris.

So fair and foul a career I have not seen. I love Céline’s novels even as I detest his racial and political views. Life can be strange.

You must be logged in to post a comment.