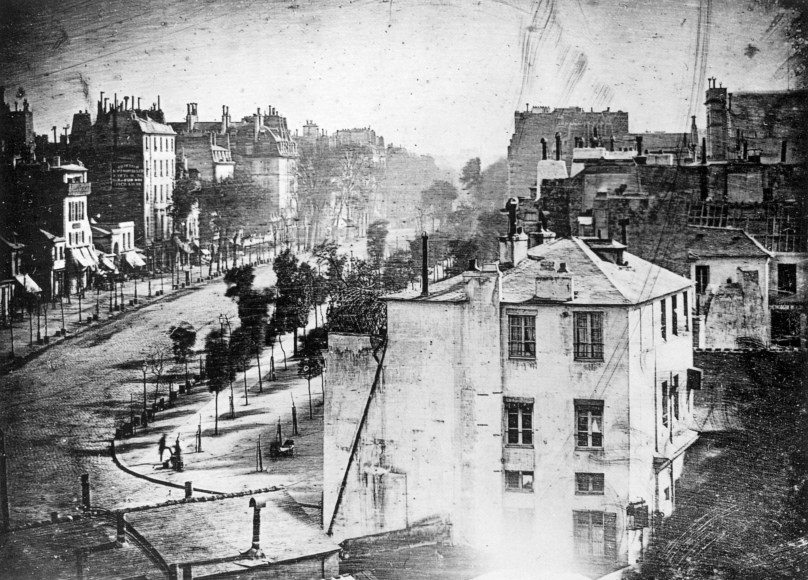

Paris’s Boulevard du Temple in 1837 or 1838

The above photograph is the first one to show a human being. There he is, in the lower left, having his shoes shined. All the pedestrians and carts and carriages have disappeared because this was an eight-hour exposure, ensuring only that static subjects could be recorded. Below is a description of Paris by Honoré de Balzac at the beginning of The Girl with the Golden Eyes (1835) that is anything but static:

One of those sights in which most horror is to be encountered is, surely, the general aspect of the Parisian populace—a people fearful to behold, gaunt, yellow, tawny. Is not Paris a vast field in perpetual turmoil from a storm of interests beneath which are whirled along a crop of human beings, who are, more often than not, reaped by death, only to be born again as pinched as ever, men whose twisted and contorted faces give out at every pore the instinct, the desire, the poisons with which their brains are pregnant; not faces so much as masks; masks of weakness, masks of strength, masks of misery, masks of joy, masks of hypocrisy; all alike worn and stamped with the indelible signs of a panting cupidity? What is it they want? Gold or pleasure? A few observations upon the soul of Paris may explain the causes of its cadaverous physiognomy, which has but two ages—youth and decay: youth, wan and colorless; decay, painted to seem young. In looking at this excavated people, foreigners, who are not prone to reflection, experience at first a movement of disgust towards the capital, that vast workshop of delights, from which, in a short time, they cannot even extricate themselves, and where they stay willingly to be corrupted. A few words will suffice to justify physiologically the almost infernal hue of Parisian faces, for it is not in mere sport that Paris has been called a hell. Take the phrase for truth. There all is smoke and fire, everything gleams, crackles, flames, evaporates, dies out, then lights up again, with shooting sparks, and is consumed. In no other country has life ever been more ardent or acute. The social nature, even in fusion, seems to say after each completed work: “Pass on to another!” just as Nature says herself. Like Nature herself, this social nature is busied with insects and flowers of a day—ephemeral trifles; and so, too, it throws up fire and flame from its eternal crater. Perhaps, before analyzing the causes which lend a special physiognomy to each tribe of this intelligent and mobile nation, the general cause should be pointed out which bleaches and discolors, tints with blue or brown individuals in more or less degree.

By dint of taking interest in everything, the Parisian ends by being interested in nothing. No emotion dominating his face, which friction has rubbed away, it turns gray like the faces of those houses upon which all kinds of dust and smoke have blown. In effect, the Parisian, with his indifference on the day for what the morrow will bring forth, lives like a child, whatever may be his age. He grumbles at everything, consoles himself for everything, jests at everything, forgets, desires, and tastes everything, seizes all with passion, quits all with indifference—his kings, his conquests, his glory, his idols of bronze or glass—as he throws away his stockings, his hats, and his fortune. In Paris no sentiment can withstand the drift of things, and their current compels a struggle in which the passions are relaxed: there love is a desire, and hatred a whim; there’s no true kinsman but the thousand-franc note, no better friend than the pawnbroker. This universal toleration bears its fruits, and in the salon, as in the street, there is no one de trop, there is no one absolutely useful, or absolutely harmful—knaves or fools, men of wit or integrity. There everything is tolerated: the government and the guillotine, religion and the cholera. You are always acceptable to this world, you will never be missed by it. What, then, is the dominating impulse in this country without morals, without faith, without any sentiment, wherein, however, every sentiment, belief, and moral has its origin and end? It is gold and pleasure. Take those two words for a lantern, and explore that great stucco cage, that hive with its black gutters, and follow the windings of that thought which agitates, sustains, and occupies it! Consider! And, in the first place, examine the world which possesses nothing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.