The following is both a long prose poem and a work of literary criticism by Canadian poet Anne Carson. It tells everything you ever wanted to know about Albertine, who appears in 5 of the 7 volumes of In Search of Lost Time. It’s called “The Albertine Workout.” The poem is taken from The London Review of Books.

1. Albertine, the name, is not a common name for a girl in France, although Albert is widespread for a boy.

2. Albertine’s name occurs 2363 times in Proust’s novel, more than any other character.

3. Albertine herself is present or mentioned on 807 pages of Proust’s novel.

4. On a good 19 per cent of these pages she is asleep.

5. Albertine is believed by some critics, including André Gide, to be a disguised version of Proust’s chauffeur, Alfred Agostinelli. This is called the transposition theory.

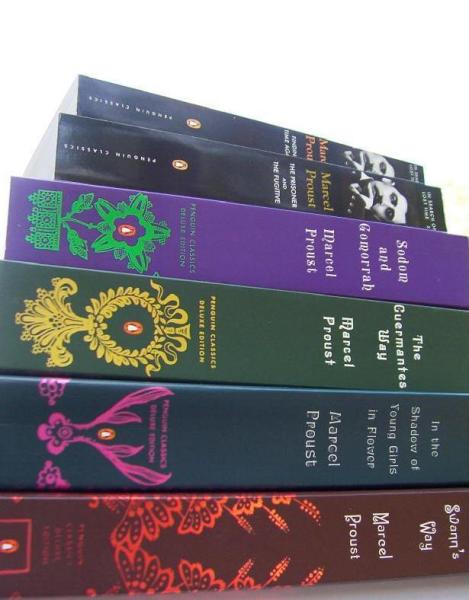

6. Albertine constitutes a romantic, psychosexual and moral obsession for the narrator of the novel mainly throughout Volume Five of Proust’s seven-volume (in the Pléiade edition) work.

7. Volume Five is called La Prisonnière in French and The Captive in English. It was declared by Roger Shattuck, a world expert on Proust, in his award-winning 1974 study, to be the one volume of the novel that a time-pressed reader may safely and entirely skip.

8. The problems of Albertine are

(from the narrator’s point of view)

a) lying

b) lesbianism,

and (from Albertine’s point of view)

a) being imprisoned in the narrator’s house.

9. Her bad taste in music, although several times remarked on, is not a problem.

10. Albertine does not call the narrator by his name anywhere in the novel. Nor does anyone else. The narrator hints that his first name might be the same first name as that of the author of the novel, i.e. Marcel. Let’s go with that.

11. Albertine denies she is a lesbian when Marcel questions her.

12. Her friends are all lesbians.

13. Her denials fascinate him.

14. Her friends fascinate him too, especially by their contrast with his friends, who are gay but very closeted. Her friends ‘parade themselves’ at the beach and kiss in restaurants.

15. Despite intense and assiduous questioning, Marcel cannot discover what exactly it is that women do together (‘this palpitating specificity of female pleasure’).

16. Albertine says she does not know.

17. Once Albertine has been imprisoned by Marcel in his house, his feelings change. It was her freedom that first attracted him, the way the wind billowed in her garments. This attraction is now replaced by a feeling of ennui (boredom). She becomes, as he says, a ‘heavy slave’.

18. This is predictable, given Marcel’s theory of desire, which equates possession of another person with erasure of the otherness of her mind, while at the same time positing otherness as what makes another person desirable.

19. And in point of fact, how can he possess her mind if she is a lesbian?

20. His fascination continues.

21. Albertine is a girl in a flat sports cap pushing her bicycle across the beach when Marcel first sees her. He keeps going back to this image.

22. Albertine has no family, profession or prospects. She is soon installed in Marcel’s house. There she has a separate bedroom. He emphasises that she is nonetheless an ‘obedient’ person. (See above on Albertine as a ‘heavy slave’.)

23. Albertine’s face is sweet and beautiful from the front but from the side has a hook-nosed aspect that fills Marcel with horror. He would take her face in his hands and reposition it.

24. The state of Albertine that most pleases Marcel is Albertine asleep.

25. By falling asleep she becomes a plant, he says.

26. Plants do not actually sleep. Nor do they lie or even bluff. They do, however, expose their genitalia.

27. a) Sometimes in her sleep Albertine throws off her kimono and lies naked.

27. b) Sometimes then Marcel possesses her.

27. c) Albertine appears not to wake up.

28. Marcel appears to think he is the master of such moments.

29. Perhaps he is. At this point, parenthetically, if we had time, which we don’t, several observations could be made about the similarity between Albertine and Ophelia – Hamlet’s Ophelia – starting from the sexual life of plants, which Proust and Shakespeare equally enjoy using as a language of female desire. Albertine, like Ophelia, embodies for her lover blooming girlhood, castration, casualty, threat and pure obstacle. Albertine, like Ophelia, is condemned for a voracious sexual appetite whose expression is denied her. Ophelia takes sexual appetite into the river and drowns it amid water plants. Albertine distorts hers into the false consciousness of a sleep plant. In both scenarios the man appears to be in control of the script yet he gets himself tangled up in the wiles of the woman. On the other hand, who is bluffing whom is hard to say.

30. Albertine’s laugh has the colour and smell of a geranium.

31. Marcel gives Albertine the idea that he intends to marry her but he does not. She bores him.

32. Albertine’s eyes are blue and saucy. Her hair is like crinkly black violets.

33. Albertine’s behaviour in Marcel’s household is that of a domestic animal which enters any door it finds open or comes to lie beside its master on his bed, making a place for itself. Marcel has to train Albertine not to come into his room until he rings for her.

34. Marcel gradually manages to separate Albertine from all her friends, whom he regards as evil influences.

35. Marcel never says the word ‘lesbian’ to Albertine. He says ‘the kind of woman I object to’.

36. Albertine denies she knows any such women. Marcel assumes she is lying.

37. At first Albertine has no individuality, indeed Marcel cannot distinguish her from her girlfriends or remember their names or decide which to pursue. They form a frieze in his mind, pushing their bicycles across the beach with the blue waves breaking behind them.

38. This pictorial multiplicity of Albertine evolves gradually into a plastic and moral multiplicity. Albertine is not a solid object. She is unknowable. When he brings his face close to hers to kiss she is ten different Albertines in succession.

39. One night Albertine goes dancing with a girlfriend at the casino.

40. When questioned about this she lies.

41. Albertine is a quick and creative liar; she may even be a natural liar. But she is a bad liar.

42. Albertine lies so much and so badly that Marcel is drawn into the game. He lies too.

43. Marcel’s jealousy, fury, envy, impotence, curiosity, pride, boredom, suffering and desire are all exasperated to their highest pitch by the game.

44. Who is bluffing whom is hard to say. (See above on Hamlet).

45. Near the end of Volume Five, Albertine finally runs away, vanishing into the night and leaving the window open. Marcel fusses and fumes and writes her a letter in which he claims he had just decided to buy her a yacht and a Rolls Royce when she disappeared, now he will have to cancel these orders. The yacht had a price tag of 27,000 francs, about $75,000, and was to be engraved at the prow with her favourite stanza of a poem by Mallarmé.

46. Albertine’s death in a riding accident on p.642 of Volume Five does not emancipate Marcel from jealousy, it removes only one of the innumerable Albertines he would have to forget. The jealous lover cannot rest until he is able to touch all the points in space and time ever occupied by the beloved.

47. There is no right or wrong in Proust, says Samuel Beckett, and I believe it. The bluffing, however, remains a grey area.

48. Let’s return to the transposition theory.

49. On 30 May 1914, French newspapers reported that Alfred Agostinelli, a student aviator, fell from his machine into the Mediterranean sea near Antibes and was drowned. Agostinelli, you recall, was the chauffeur whom Proust in letters to friends admitted that he not only loved but adored. Proust had bought Alfred the aeroplane, which cost 27,000 francs, about $75,000, and had had it engraved on the fuselage with a stanza of Mallarmé. Proust also paid for Alfred’s flying lessons and registered him at the flying school under the name Marcel Swann. The flying school was in Monaco. In order to spy on Alfred while he was there, Proust sent another favourite manservant, whose name was Albert.

50. Compare and contrast Albertine’s sudden fictional death by runaway horse with Alfred Agostinelli’s sudden real-life death by runaway plane. Poignantly, both unfortunate beloveds managed to speak to his/her lover from the wild blue yonder. Agostinelli, before setting out for his final flight, had written a long letter, which Proust was heartbroken to receive the day after the plane crash. Transposed to the novel, this exit scene becomes one of the weirdest in fiction.

51. Several weeks after accepting the news that Albertine has been thrown from her horse and killed, Marcel gets a telegram:

You think me dead but I’m alive and long to see you! affectionately Albertine.

Marcel agonises for days about this news and debates with himself whether to resume relations with her, only to realise that the signature on the telegram has been misread by the telegraph operator. It is not from Albertine at all but from another long-lost girlfriend whose name (Gilberte) shares its central letters with Albertine’s name.

52. ‘One only loves that which one does not entirely possess,’ says Marcel.

53. There are four ways Albertine is able to avoid becoming possessable in Volume Five: by sleeping, by lying, by being a lesbian or by being dead.

54. Only the first three of these can she bluff.

55. Proust was still correcting a typescript of La Prisonnière on his deathbed, November 1922. He was fine-tuning the character of Albertine and working into her speech certain phrases from Alfred Agostinelli’s final letter.

56. It is always tricky, the question whether to read an author’s work in light of his life or not.

57. Granted the transposition theory is a graceless, intrusive and saddening hermeneutic mechanism; in the case of Proust it is also irresistible. Here is one final spark to be struck from rubbing Alfred against Albertine, as it were. Let’s consider the stanza of poetry that Proust had inscribed on the fuselage of Alfred’s plane – the same verse that Marcel promises to engrave on the prow of Albertine’s yacht, from her favourite poem, he says. It is four verses of Mallarmé about a swan that finds itself frozen into the ice of a lake in winter. Swans are of course migratory birds. This one for some reason failed to fly off with its fellow swans when the time came. What a weird and lonely shadow to cast on these two love affairs, the fictional and the real; what a desperate analogy to offer of the lover’s final wintry paranoia of possession. As Hamlet says to Ophelia, accurately but ruthlessly, ‘you should not have believed me.’

58.

Un cygne d’autrefois se souvient que c’est lui

Magnifique mais qui sans espoir se délivre

Pour n’avoir pas chanté la région où vivre

Quand du stérile hiver a resplendi l’ennui

(Mallarmé, ‘Le vierge, le vivace et le bel aujourd’hui’)

a swan of olden times remembers

that it is he:

the one

magnificent but

without hope setting himself free

for he failed to sing

of a region for living

when barren winter

burned all around him with ennui

59. ‘Everything, indeed, is at least double.’

La Prisonnière p.362

You must be logged in to post a comment.