Between 1803 and 1805, Napoleon started planning for the invasion of England. His planning was financed by the sale of the Louisiana Purchase to the fledgling American Republic. Yet, the invasion never took place. Why?

According to Louis Antoine Fauvelet de Bourrienne, a French diplomat close to him, when asked why the invasion was called off, Bonaparte replied:

A great battle will be fought, which I shall gain; but I must count upon 30,000 men killed, wounded or taken prisoners. If I march on London a second battle will be fought. I shall suppose myself again victorious. But what shall I do in London with an army reduced three/fourths and without hope of reinforcements. It would be madness.

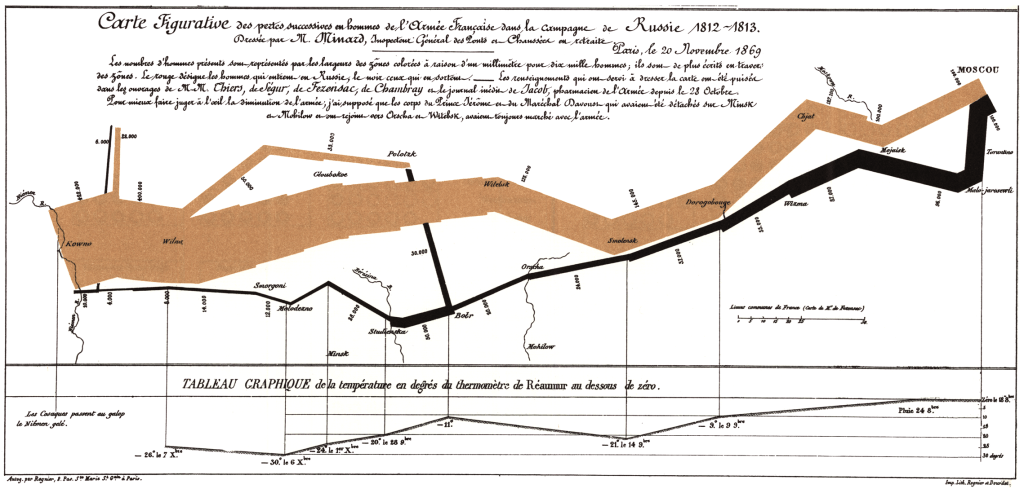

It is unfortunate that Napoleon did not apply the same reasoning in his invasion of Russia a few years later. There is a famous chart which shows graphically what happened to the French forces on the way to Moscow (shown in brown) and during the retreat (shown in black). The thickness of the line graphically illustrates the truth of Napoleon’s decision not to invade Britain.

Charles Minard’s Famous Graph of the Failure of Napoleon’s Russian Invasion

Somehow, over a period of some few years, did Napoleon’s military ability suddenly vanish?

You must be logged in to post a comment.