Art Deco was born in France in the period immediately after the First World War and lasted roughly up to the start of the Second World War. According to British art historian Bevis Hiller, it was “an assertively modern style [that] ran to symmetry rather than asymmetry, and to the rectilinear rather than the curvilinear; it responded to the demands of the machine and of new material [and] the requirements of mass production.” Its name comes from the French Arts Décoratifs, from the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes held in Paris.

It was not an art of the people. Rather it was associated with the wealthy, for whom optimism is a kind of religion. According to Wikipedia, it “represented luxury, glamour, exuberance and faith in social and technological progress.”

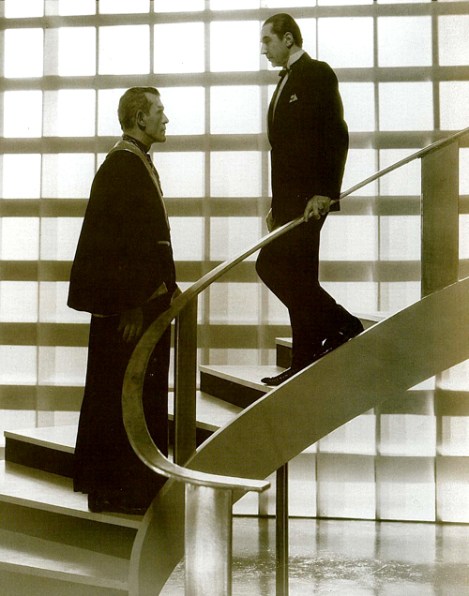

Our visit to the Mullin Automotive Museum in Oxnard last Saturday set me to thinking: To whom did Art Deco really belong? I am reminded of the strange mansion set of Edgar G. Ulmer’s The Black Cat (1934) starring Béla Lugosi and Boris Karloff as Hjalmar Poelzig, the archetypal Art Deco man.

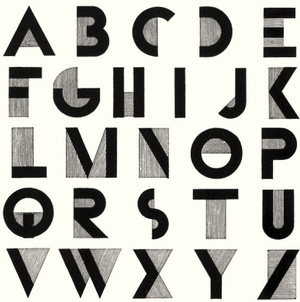

There were even Art Deco print fonts, such as the following:

Think about the lavish movie sets of the Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers movies, set in lavish Art Deco hotels in Europe and elsewhere. These were not places where people such as myself would feel highly uncomfortable. It was a world of tuxedos, butlers, fantastic dance floors, and a spic-and-span shine that almost glistened. It was “high tech” for the technology that was then extant, which manifested itself in the luxury French automobiles on display at the Mullin Museum.

Some of it filtered down to the middle class, but for the most part it represented an aspiration to empyrean social realms beyond the reach of most people.

Still, it could be incredibly beautiful, as in the paintings of Tamara de Lempicka, architecture such as the Chrysler Building in New York, industrial design, textiles, jewelry, and—of course—the cinema. I believe that we are just beginning to understand this movement.

You must be logged in to post a comment.