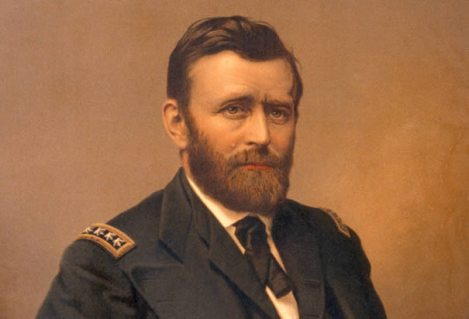

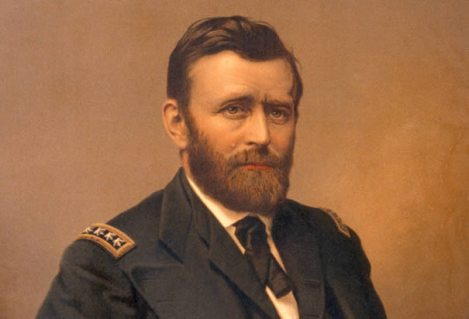

Union General Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant was an altogether unprepossessing man. He didn’t have the swagger or gravitas of such Union generals as McDowell, Pope, McClellan, Burnside, Hooker, or Meade; but on the other hand, he was not a coward, a poltroon, or pathologically cautious either. His successes were due not only to his pertinacity, but to a grim secret that he knew and made use of as head of the Army of the Potomac.

Yes, the South had the more dashing generals, but they were on the wrong side when it came to the numbers. You see, the North had a larger population of eligible males to sacrifice to death, disability, and capture than the South. The South had, for all practical purposes, 100% conscription. At the end of the war, there were still at least 2 million eligible men who hadn’t worn the blue uniform. Take a look at this website by the Civil War Trust or charts and tables on Civil War casualties.

This Chart Says It All

The other factor was that Grant never ran. At the end of the battle, he was still there and still game for more bloodshed—not for the sake of shedding blood, but for the sake of ultimate victory.

I have been reading the second volume of Shelby Foote’s The Civil War: A Narrative. Even with his Confederate sympathies, Foote could appreciate Grant’s grand strategy at Vicksburg. If the North won Vicksburg, the whole Trans-Mississippi South would be lost. The problem was: How to get at it. The most obvious way was to invade Mississippi and take it from the rear. Unfortunately, that failed; and in any case the area was controlled by the South’s most ingenious and fierce commander of cavalry, Nathan Bedford Forrest. (After the war, Forrest was one of the founders of the Ku Klux Klan.)

Grant was not afraid to fail, and he failed a total of seven or eight times before he found a way of marshaling his army and navy forces to effect a landing on the eastern side of the Father of Waters, well out of the way of Forrest’s cavalry. He made straight for Jackson, Mississippi, where he wrecked the railroad lines that supplied the Confederates at Vicksburg. Along the way back toward Vicksburg, he fought two battles at Champion Hill and the Big Black River. Then and only then did he directly besiege Vicksburg. From then on, it was pretty much a matter of starving the rebels until they surrendered early in July.

It was right around then that the North won its decisive victory at Gettysburg.

It wasn’t long before Lincoln concluded that, in Grant, he had a general who could outfight Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. That is exactly what he proceeded to do in what has come to be known as his Overland Campaign. It didn’t matter how many men he lost jat battles such as the Wilderness, the North Anna, Spotsylvania Court House, and Cold Harbor just so long as he didn’t fall back after each battle, as the Army of the Potomac was wont to do. He not only did not fall back: He pushed Lee’s forces step by step closer to the final showdown in front of Richmond. And by then, it was all over.

Too bad that Grant made such a terrible President. He was a smart man, and a great military leader, but none of us are perfect.

You must be logged in to post a comment.