George Jetson’s Neighborhood

If any writer alive today has a handle on the future—what it is likely to be—that writer is William Gibson, the author of Neuromancer and the inventor of the term cyberspace. I have just finished reading his book of essays, entitled Distrust That Particular Flavor. In a talk delivered o the Book Expo America in 2010, he wrote:

But I really think [that pundits are] talking about the capital-F Future, which in my lifetime has been a cult, if not a religion. People my age are products of the capital-F Future. The younger you are, the less you are a product of that, If you’re fifteen or so, today, I suspect you inhabit a sort of endless digital Now, a state of atemporality enabled by our increasingly efficient prosthetic memory. I also suspect that you don’t know it, because, as anthropologists tell us, one cannot know one’s own culture.

The Future, capital-F, be it crystalline city on a hill or radioactive postnuclear wasteland, is gone. Ahead of us, there is merely … more stuff. Events. Some tending to the crystalline, some to the wasteland-y. Stuff: the mixed bag of the quotidia.

I think of Gibson’s capital-F Future as being more along the line of the old The Jetsons animated television program or the novels of H. G. Wells or Isaac Asimov. The future presented in those works is more a reflection of their creators’ times, and not our own.

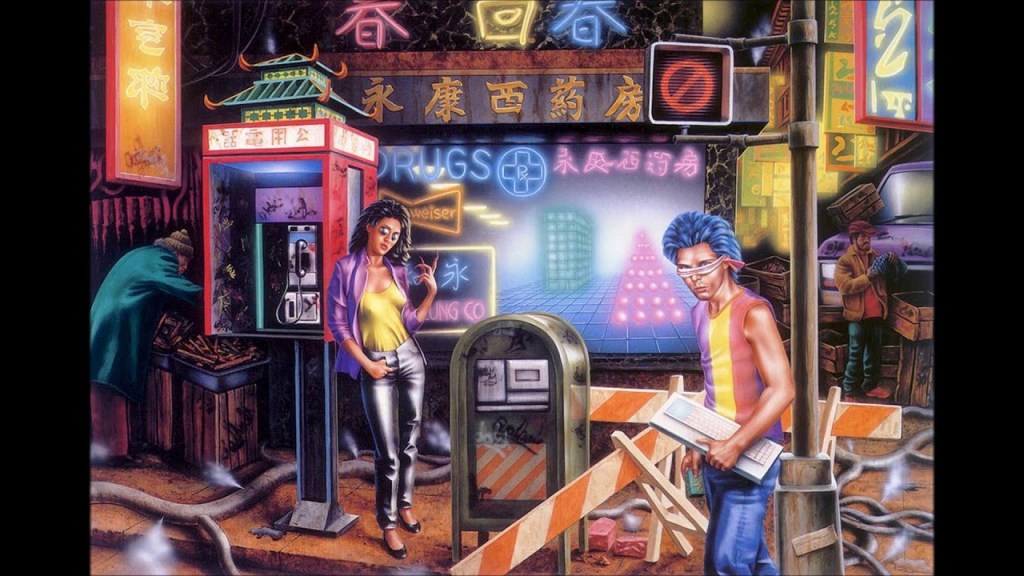

William Gibson

I think that, because of his belief regarding the future, Gibson’s more recent novels have been less science fiction-y. Books such as Zero History are set in what appears, on one hand, to be the present—but instead are set in some not-too-distant future with multiple hooks to our present.

In a number of essays, Gibson examines our strange atemporal present, with fascinating essays on Tokyo (“My Own Private Tokyo”) and Singapore (“Disneyland with the Death Penalty”).

You must be logged in to post a comment.