Argentinians Have Made Up Some of Their Own Saints

This comes from a post on Multiply.Com which I wrote on August 18, 2011. Some changes have been made:

Oh, oh! I’ve been thinking about Argentina again, and that means you’re going to hear about some more really obscure (but, IMHO fascinating) stuff.

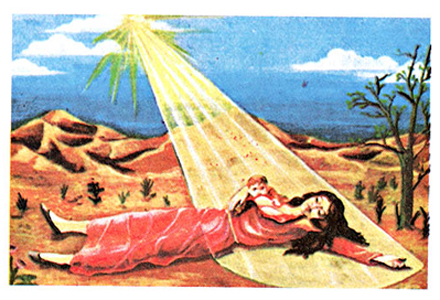

To begin with, Argentina is such a Catholic country that it had to create additional saints native to its own soil. Let’s begin with La Difunta Correa, which means, literally, the Dead Correa:

According to popular legend, Deolinda Correa was a woman whose husband was forcibly recruited around the year 1840, during the Argentine civil wars. Becoming sick, he was then abandoned by the Montoneros [partisans]. In an attempt to reach her sick husband, Deolinda took her baby child and followed the tracks of the Montoneros through the desert of San Juan Province. When her supplies ran out, she died. Her body was found days later by gauchos that were driving cattle through, and to their astonishment found the baby still alive, feeding from the deceased woman’s “miraculously” ever-full breast. The men buried the body in present-day Vallecito, and took the baby with them. [from Wikipedia]

All over the country, there are roadside shrines to La Difunta Correa, many surrounded by gifts left by truck drivers and travelers in a hope for a safe journey to their destination. Remember that Argentina is the eighth largest country on earth, and that distances can be farther than one imagines, especially on unpaved ripio roads.

There are two other popular saints with shrines all across the nation: Gauchito Gil (“Little Gaucho Gil”) and El Ángelito Milagroso (“The Little Miraculous Angel”), a.k.a. Miguel Ángel Gaitán.

Gauchito Gil hails from the state of La Rioja near the Bolivian border. A farmworker, Gil was seduced by a wealthy widow. When the police chief, who also had a thing for the widow, and her brothers came after Gil, he joined the army in the War of the Triple Alliance against Paraguay (perhaps the bloodiest war ever fought in the Americas, with the exception of our own Civil War). When he returned home, the Army came after him to join in one of Argentina’s many civil wars. Not to put too fine a point on it, the Gauchito deserted. He was discovered by the police, who wanted to execute him. Whereupon Gil prophesied to the head of the police detail that if he were merciful, the officer’s child, who was gravely ill, would get better. Instead of being shown mercy, Gil was executed.

When he returned home, the police officer found that his son was indeed very ill. So he prayed to Gauchito Gil, and his son got better. It was this police officer who returned to the scene of the execution, gave Gil a proper burial, and built a shrine in his memory. Today there are hundreds of such shrines scattered throughout the country.

By the way, the Gauchito is not the only deserter hero in Argentina’s past. Perhaps the national epic is Martin Fierro by José Hernández, about a gaucho who deserts from the so-called “Conquest of the Desert”—really a war of genocide against the native tribes of the Pampas—and is pursued by the police militia.

The Nineteenth Century in Argentina was unusually bloody, what with civil war, wars against the native peoples, and wars against other countries such as Paraguay and Brazil. So it is not unusual to find deserters as heroes, which is unthinkable in Europe and North America.

Finally, there is another La Rioja “saint” named Miguel Ángel Gaitán, El Ángelito Milagroso, who died at the tender age of one in 1967. When his body didn’t rot, the locals thought that meant it was supposed to be exposed for veneration—and so it was.

34.052234

-118.243685

You must be logged in to post a comment.