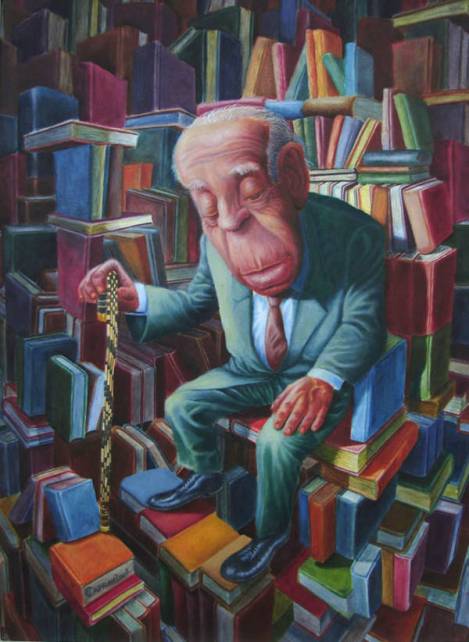

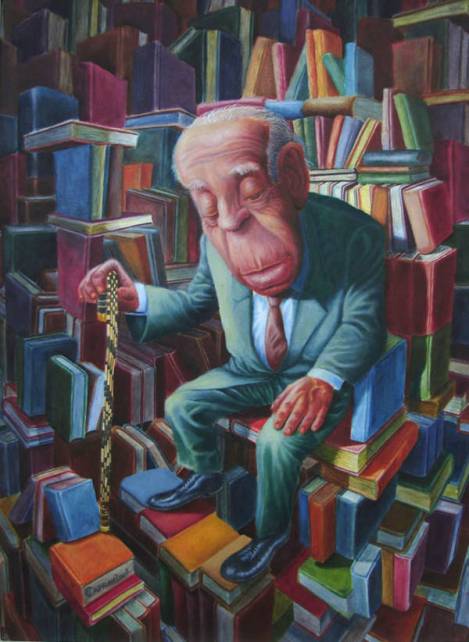

Jorge Luis Borges and His Books

Blindness was a curse in Jorge Luis Borges’s family. Not only his father, but his grandfather and great-grandfather all died blind. Fortunately for us, Borges had lived for more than fifty years before the gathering darkness prevented him from picking a book from his shelf and reading it. Because he lived on for thirty-five years or so longer, the Argentinian writer and poet managed to find a role for himself that would help keep his amazing erudition alive and produce works of interest to a worldwide public that was just beginning to discover him.

Enter Borges the interviewee. I first experienced this in Paul Theroux’s The Old Patagonian Express, when the American author describes a meeting with Borges in Buenos Aires. It began with Borges requesting that Theroux read some passages from Kipling to him and went on from there. From this point on, I continued finding published interviews, and I started collecting them alongside his original poems and stories, whose output diminished as he aged.

In a brief interview with Amelia Barili, he is asked about the meaning of life:

If life’s meaning were explained to us, we probably wouldn’t understand it. To think that a man can find it is absurd. We can live without understanding what the world is or who we are. The important things are the ethical instinct and the intellectual instinct, are they not? The intellectual instinct is the one that makes us search while knowing that we are never going to find the answer. I think Lessing said that if God were to declare that in His right hand He had the truth and in his left hand He had the investigation of the truth, Lessing would ask God to open His left hand—he would want God to give him the investigation of the truth, not the truth itself. Of course he would want that, because the investigation permits infinite hypotheses, and the truth is only one, and that does not suit the intellect, because the intellect needs curiosity. In the past, I tried to believe in a personal God, but I do not think I try anymore. I remember in that respect an admirable expression of Bernard Shaw: “God is in the making.”

Willis Barnstone’s Borges at 80: Conversations has this little gem. When asked about the wrong women he has loved and the wrong days he has spent, Borges replied:

All those things, the wrong women, the wrong actions, the wrong circumstances, all those are tools to the poet. A poet should think of all things as being given him, even misfortune. Misfortune, defeat, humiliation, failure, those are our tools. You don’t suppose that when you are happy, you can produce anything. Happiness is its own aim.

As one who has personally suffered from dictators—Juan Perón made him a poultry inspector for the markets of Buenos Aires—Borges describes what he thinks of them:

It really seems a childish idea, don’t you think? I believe the idea of giving orders and being obeyed is more to be associated with a child’s mind than that of a man. I don’t think dictators generally are very intelligent people. Fanaticism can lead to it too. Take Cromwell’s case, for example: I think he was a Puritan; he was a Calvinist and believed he had every right. But in the case of more recent dictators, I don’t think they’ve been motivated by fanaticism. I think they were impelled by histrionic zeal, by the desire for applause, for being obeyed, and perhaps by the mere childish craving for publicity, which is a craving I don’t understand. [Sounds a lot like Trumpf, no?]

This last comes from Fernando Sorrentino’s Seven Conversations with Jorge Luis Borges, one of the better collections of interviews with Borges.

Jorge Luis Borges was, fortunately, a great conversationalist. I still like to pick up one or other of his interviews and re-read it just for the pleasure of the man’s company.

34.052234

-118.243685

You must be logged in to post a comment.