Tony Randall as the Medusa in 7 Faces of Dr Lao (1964)

Oh, God, what is he on about now? Twonky? What is twonky?

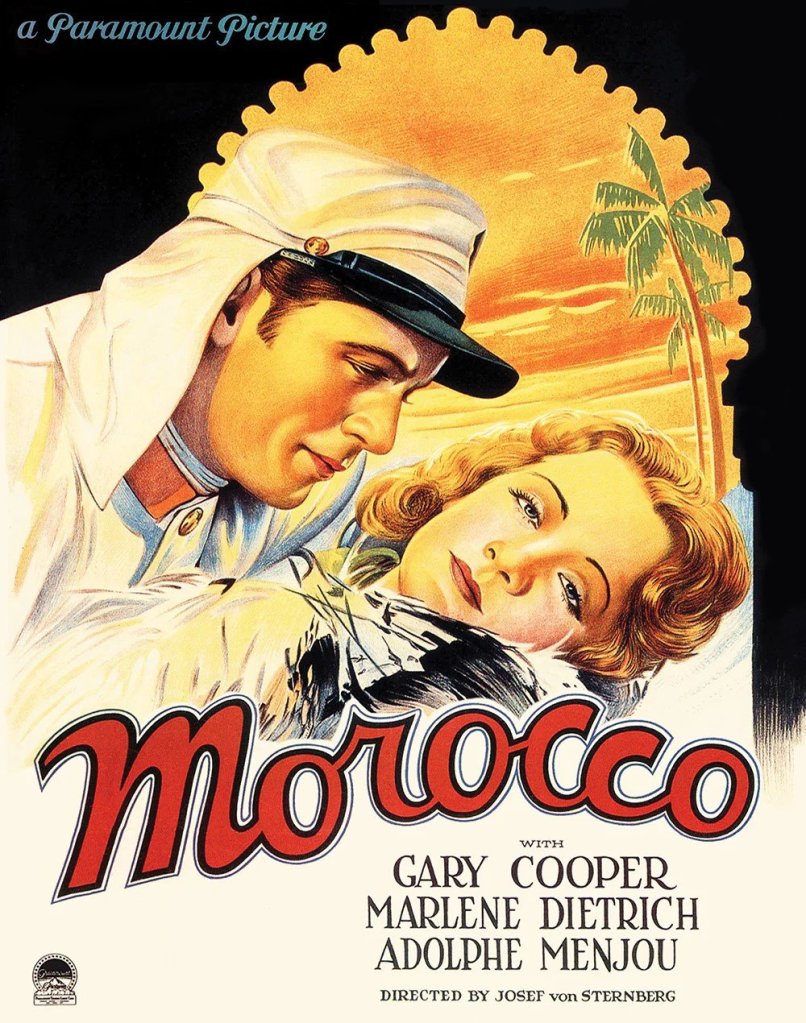

You well know that there are films that you love but to which you cannot ascribe a high level of artistic excellence. I refer to them as twonky films. For me, a perfect example is George Pal’s 7 Faces of Dr Lao, produced at MGM. In it, Tony Randall actually plays eight roles: the inscrutable Dr Lao (pronounced LOH) himself, the magician Merlin, the god Pan, the Talking Serpent, Medusa, Apollonius of Tyana, the Abominable Snowman, and (uncredited) himself as a seated member of the audience.

In the last seven years, I have seen 7 Faces of Dr Lao four times and I’m still not tired of it. I will continue to see it and enjoy it whenever I can. I even read the book it was based on: Charles G. Finney’s The Circus of Dr Lao. (As a matter of fact, I think I’ll probably re-read the book pretty soon.)

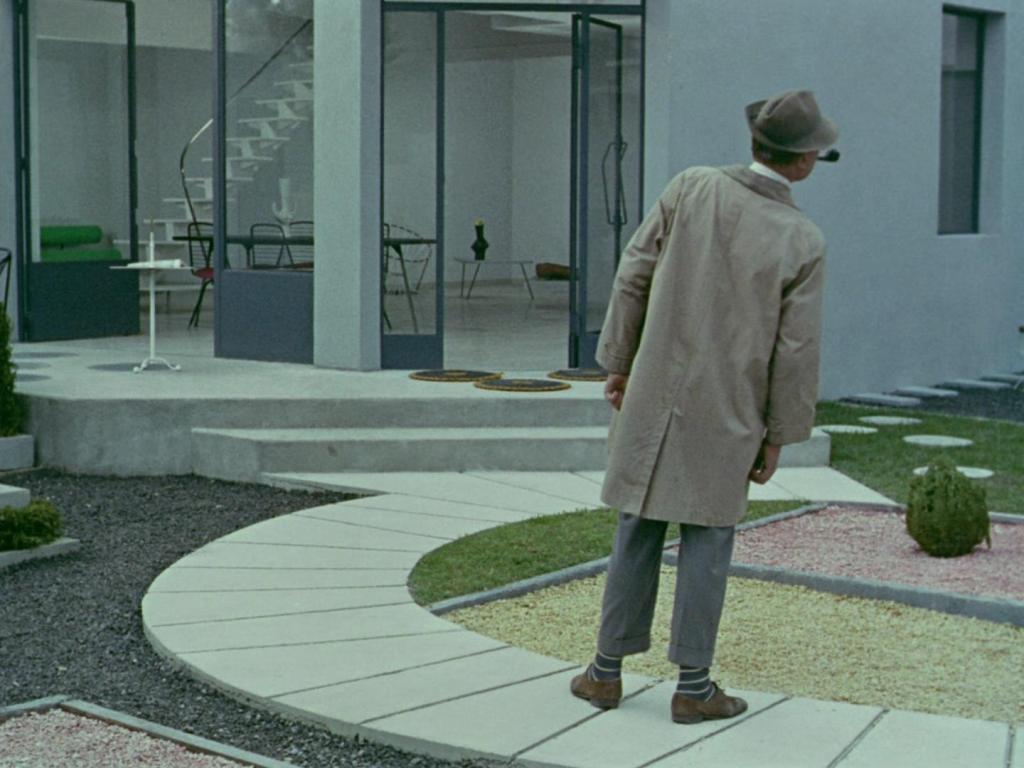

Now where does this term twonky come from? In 1953, Arch Oboler directed a science fiction film entitled The Twonky starring Hans Conried. According to the Internet Movie Database (IMDB), the plot concerns a “Tweedy college professor [who] discovers his new TV set is animate, apparently possessed by something from the future, and militantly intent on regulating his daily life.”

I have not seen the film but it sounds pretty twonky to me.

There are many other films (and, dare I say it, books) that I would consider to be twonky. I’m thinking of Ed Wood’s Plan 9 from Outer Space, Showgirls, Popeye cartoons, and virtually the entire filmography of Roger Corman and William Castle.

Interestingly, there is a generation gap between the bad films I like and the bad films a Gen Z’er would like. That’s understandable because young people were raised to love a different kind of bad film. Even my younger brother (by six years) grew up loving Clutch Cargo and Huckleberry Hound cartoons, which I considered too unsophisticated for my tastes.

You must be logged in to post a comment.