Perhaps the most interesting destination on our recent trip to the Eastern Sierras was the Ancient Bristlecone Pine Forest in the Inyo National Forest in the White Mountains. The living bristlecones are as old as 4,862 years old. Using the science of dendrochronology, or tree-ring dating, it is possible to go back almost 10,000 years comparing overlapping dry/wet year rings with those of standing dead bristlecones and even fallen dead bristlecones. Because of the climate near the peaks of the White Mountains is so dry and windy, fungi that destroy the dead wood are slow to take hold.

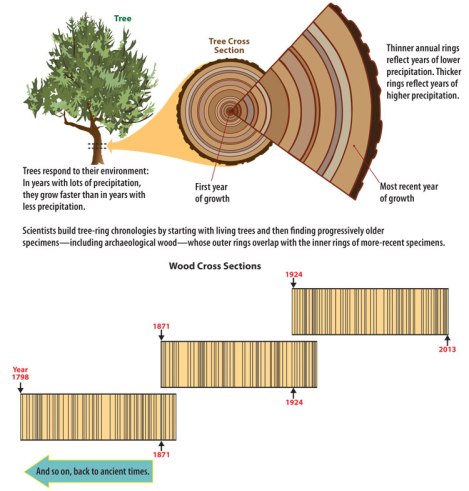

The following illustration shows how the sequencing of dry/wet years going back in time works:

Using these methods, it is possible to scientifically disprove Bishop Ussher’s contention that the creation dated back to 4004 B.C. Dendrochronologists can take wooden lintels from Maya ruins and prove when the piece of wood was cut down. They have shown that the ruins of Stonehenge, for example, are a thousand years older than previously thought—which knocks into a cocked hat the anthropological theory that European civilization had its cultural origins in the Middle East.

Martine and I took the Discovery Trail from the Schulman Grove Visitor’s Center at the Ancient Bristlecone Pine Forest. We were unable to finish the trail, because it kept going to higher elevations, and I was having some trouble with breathing and light-headedness. Fortunately, these symptoms became less pronounced as we went about a hundred feet lower.

At the Visitor’s Center, I bought a bookmark with “Advice from a Bristlecone Pine,” which consisted of the following:

- Sink your roots into the earth

- Keep growing

- Be content with your natural beauty

- Weather adversity

- Go out on a limb

- Its OK to be a little gnarly

- Honor your elders!

That second last bit about being a little gnarly is particularly interesting. The tall straight bristlecone pines are never as old as the twisted trunks and branches of trees that grow closer to the ground. Part of these trees could be bead, but they contain live branches that can continue living until something kills them. Amazing trees!

You must be logged in to post a comment.