Alan Turing on a £10 Banknote Design (Rejected!)

No, no such £10 banknote exists. It would have been a nice idea, though. After all, Alan Mathison Turing contributed as much, if not more, to modern life as Albert Einstein, Charles Darwin, or Niels Bohr. During the Second World War, the Germans had an encryption machine which generated a code that was thought to be unbreakable. At Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire, the British ran a decrypting project whose star quickly became Turing. His solution was brilliant: Create a universal computing machine that could not only solve the code, but ultimately any code constructed along logical lines. Such a machine was referred to as a Turing machine. We now call it a computer.

During the middle of the War, Turing’s machine, called Colossus, began breaking the Nazi code, and continued to do so through the war. The trick was not to react in such a way that the Germans knew that the code was cracked. Bletchley Park worked closely with British MI6 (Military Intelligence, Section 6) to feed selected information carefully to the Russians and to their own allied forces. During the course of the War, the Germans never did find out that they were communicating as much with Sir Winston Churchill as with their forces in the field. It is thought that Turing’s invention saved the lives of millions of men and shortened the war by as much as two years. (It’s not provable, of course, but it’s nice to think so.)

A German Enigma Machine

Why Alan Turing is not better known is owing to a shameful episode in history. The Cambridge mathematician who was as much of a hero as any allied general in the conflict was a homosexual, and under the laws in Britain, was a criminal. In 1952, he was caught and offered the choice of prison or accepting hormone therapy. He chose the latter, but the result of taking the primitive medicines, he lost his edge as one of the greatest mathematicians in history. In 1956, he committed suicide rather than continue the therapy.

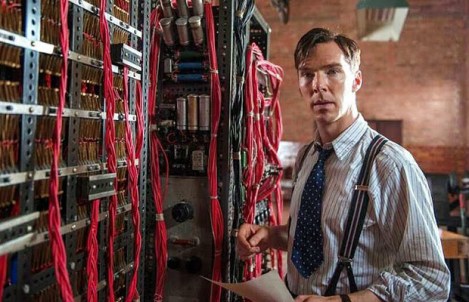

Yesterday, I reviewed The Imitation Game, which tells the story of Turing at Bletchley park. While it simplifies what actually happened, it is in large part true to its subject.

34.052234

-118.243685

You must be logged in to post a comment.