Buenos Aires: Traffic on Calle Florida

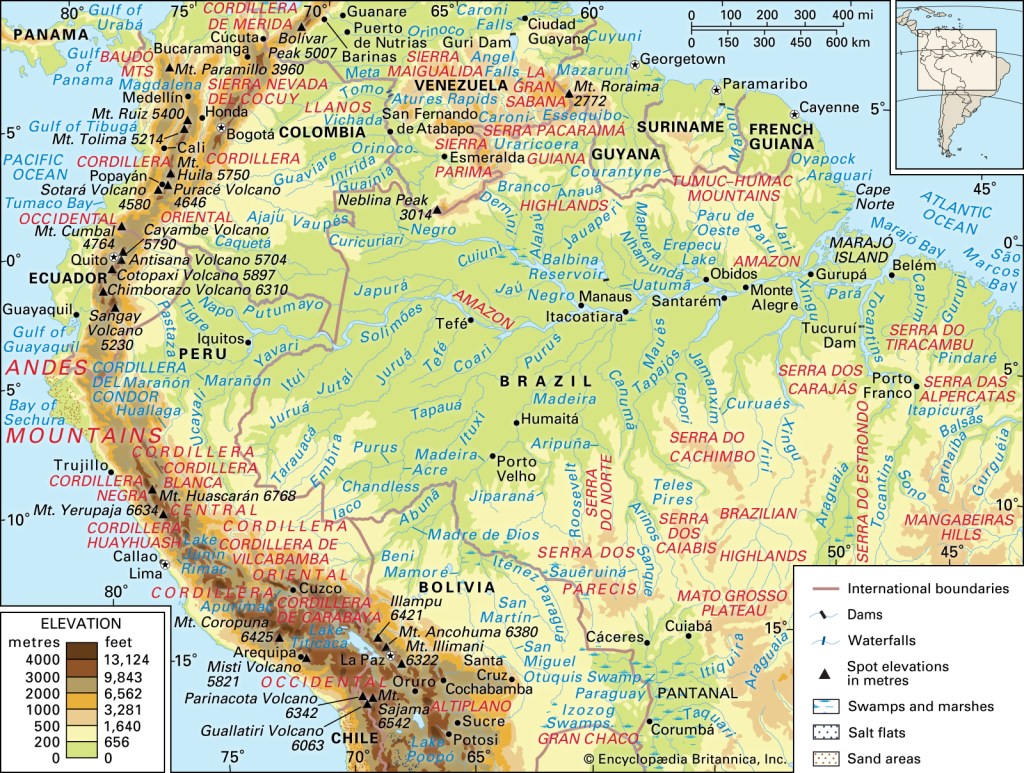

It has now been ten years since my last visit to Argentina. Cristina Kirchner was still President of the Republic. I had an itinerary that included a visit to the Foz de Iguazu by the border with Brazil, the Patagonian resort of San Carlos Bariloche, and a bus and boat trip over the Andes to Puerto Varas in Chile.

I revisited the spectacular cemetery at Recoleta where Eva Perón is buried and the port of Tigre by the delta of the Paraná River. On my way to the bus station in Retiro, a serious attempt was made to pick my pocket at a time when I was carrying $2,000 in Argentinean pesos. (I quickly sidestepped to the right and hailed a cab.)

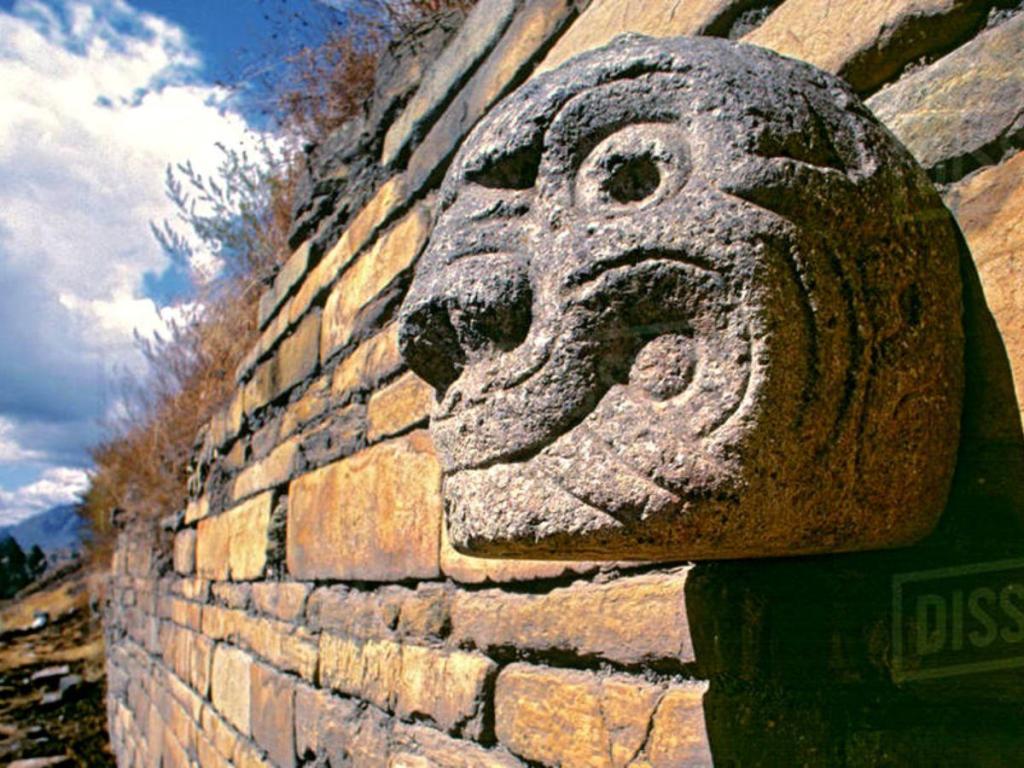

Funerary Statue at Recoleta Cemetery

I got violently ill at a hotel by the Congreso after eating a dubious steak dinner the night before, but I managed nonetheless to catch my bus to Puerto Iguazu and got better after a 10-hour bus ride that passed hundreds of fields where yerba mate was growing.

In sum, it was a great trip. As long in the tooth as I am, I would jump at the chance to visit Argentina again. The long plane ride over the Andes could be brutal, but the country is endlessly fascinating. I especially love Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego.

At the Puerto Iguazu Bus Station

Most Americans have little or no idea of what South America is really like. Over the last twenty years, I have been to Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Peru, and Ecuador and enjoyed just about every minute of my travels there.

You must be logged in to post a comment.