Definitely on my travel bucket list is one of South America’s two landlocked countries (the other one is Bolivia, which had a seaport on the Pacific until they lost it in an 1870s war with Chile). I am speaking, of course, of Paraguay, which is surrounded by Argentina, Brazil, and Bolivia. I personally know no one who has been to Paraguay, yet I am yearning to visit it.

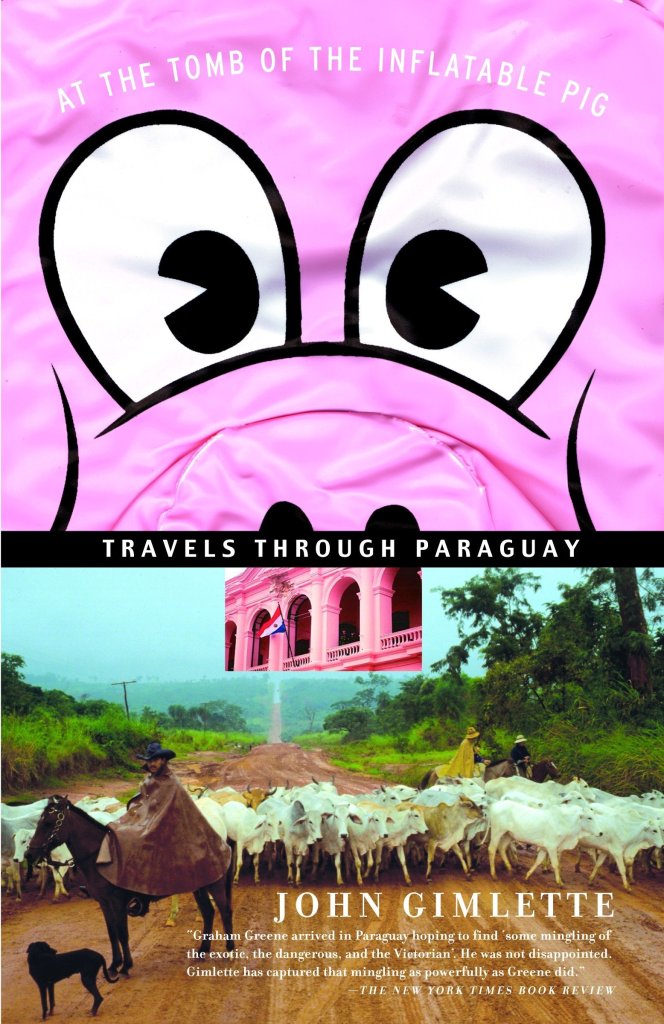

What piqued my interest was John Gimlette’s At the Tomb of the Inflatable Pig, which captures the insane history of this little known country, which is known for:

- The Paraguayan War (1864-1870) against, simultaneously, Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay, in which 50% of the population lost their lives.

- The Chaco War (1930s) against Bolivia, in which two armies confronted each other in a waterless desert and which, surprisingly, Paraguay won despite horrendous casualty rates.

- The dictatorship of Alfredo Stroessner (1954-1989) in which the country welcomes fleeing Nazis.

While it is theoretically possible to fly into the capital, Asunción, I would rather enter by bus from Argentina. When I visited Iguazu Falls in 2015, I was only a few miles from Ciudad del Este, which is a known hangout of smugglers and Hezbollah terrorists—but I chose not to visit it at that time. (Actually, probably never would suit me.)

If I went to Paraguay, I would be interested in visiting the old Jesuit missions that were destroyed by the Brazilians. At one time, in the 18th century, Paraguay was controlled by the Jesuits and was considered a paradise on earth. To corroborate, read Voltaire’s Candide and see Roland Joffe’s 1986 film The Mission with Robert De Niro and Jeremy Irons. But after the missions were destroyed, things went bad.

And I would like to stay in Asunción sipping Tereré, a cold preparation made with Yerba Mate. If I had time, I would like to see a little bit (a very little bit) of the Chaco region in the northwest.

You must be logged in to post a comment.