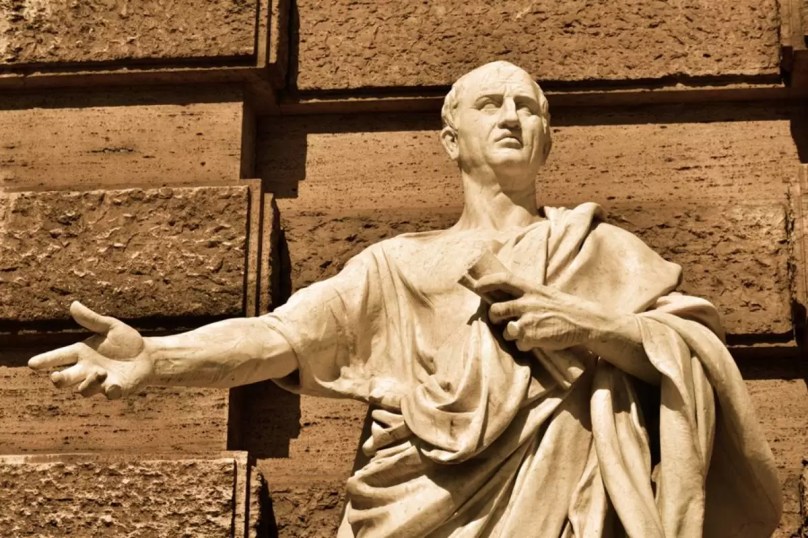

Roman Senator Marcus Tullius Cicero (100-43 BCE)

How many letters and journals have come down to us from Ancient Egypt or Classical Greece or Biblical Palestine? None. Consequently, our view of their respective civilizations is an incomplete one. For the last years of the Roman Republic, however, we have a voluminous orator, letter writer, and philosopher who was very much at the center of the action.

Marcus Tullius Cicero was one of the most powerful members of the Roman Senate. From him, we have political orations, speeches for the prosecution or defense of murder trials, essays on the gods and growing old (among other subjects), and letters to friends and political associates. In particular, his letters to his friend Atticus give us a picture of his times such as we do not have from any other ancient civilization.

What is more, his works are eminently readable today. In fact, his oration attacking Mark Antony was so effective that the Roman general promptly sent out an assassin to shut him up permanently.

I have just finished viewing the HBO/BBC co-produced mini-series called Rome (2005-2007) which covered the last days of the Roman Republic. The twenty-two episodes include incidents in the life of Julius Caesar, Augustus Caesar, Mark Antony, Pompey the Great, Brutus, Cassius, Cleopatra, and Cicero.

David Bamber as Cicero in the HBO/BBC Mini-Series Rome

Both the mini-series and Cicero’s own writings portray the senator as a deeply divided individual. He was a follower of Gnaeus Pompey and was with him when he lost to Julius Caesar at Pharsalus. Then he sided with Brutus, Cassius, and the other slayers of Julius Caesar and was with them at the Battle of Philippi. That did not sit well with Antony and Octavian (later renamed Augustus), who agreed to his demise.

Even more than two thousand years later, we can see clearly that Cicero was a follower of the old, traditional senate and of Cato the Younger, who committed suicide after Philippi. In 63 BCE, he led the overthrow of the conspiracy of Lucius Sergius Catiline, having several of the participants executed without trial. Ever after, he was disappointed that the people did not express sufficient gratitude. It was clearly a case of, “Yes, but what have you done for us lately?”

I strongly urge you to read some of the excellent Penguin translations of Cicero’s work and, if you have time, view the Rome mini-series, which is still available on HBO.

You must be logged in to post a comment.