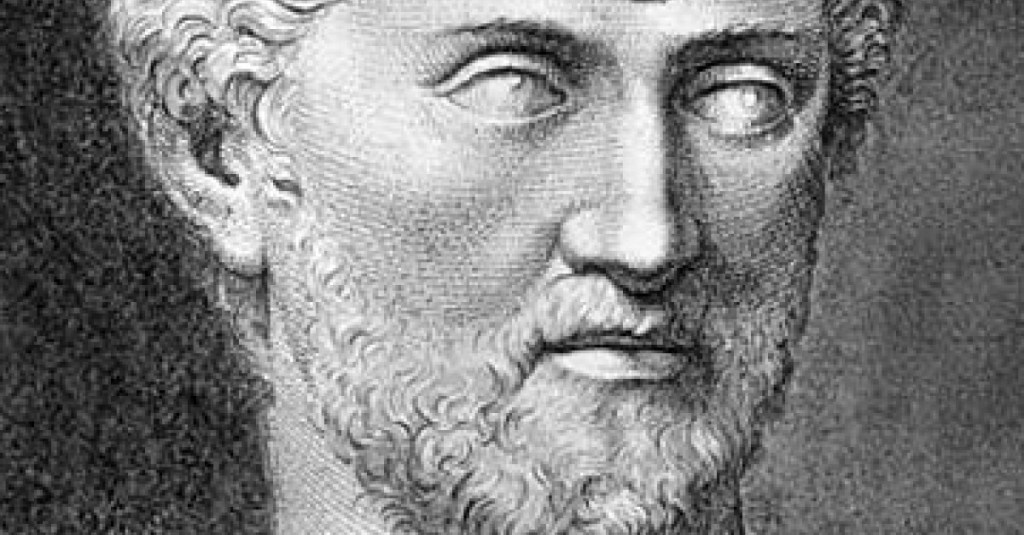

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (AD 121-180)

When Edward Gibbon came to write The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, he began with what he regarded as a golden age in the affairs of men, namely, the reign of the five “good” Antonine emperors. These were Nerva (AD 96-98), Trajan (AD 98-117), Hadrian (AD 117-138), Antoninus Pius (AD 138-161), and Marcus Aurelius (AD 161-180).

Among all the Roman emperors, it was only Marcus Aurelius who, in his Meditations, published a work of Stoic philosophy that is read to this day. It was he who wrote:

When you first rise in the morning tell yourself: I will encounter busybodies, ingrates, egomaniacs, liars, the jealous and cranks. They are all stricken with these afflictions because they don’t know the difference between good and evil. Because I have understood the beauty of good and the ugliness of evil, I know that these wrong-doers are still akin to me . . . and that none can do me harm, or implicate me in ugliness—nor can I be angry at my relatives or hate them. For we are made for cooperation.

Today was the last day at the Getty Villa in Pacific Palisades for a 3½-pound gold head of the emperor to be on display, so I felt I just had to see it. So I drove out to the Villa with my 90-year-old neighbor Luis to see it and check out the permanent collections as well.

It was well worth seeing, even though I developed a bad case of museum legs which tired me out after five hours. I visit the museum two or three times a year, and i love it more each time. And now I feel I should re-read the Meditations. I mean, how many world leaders ever wrote a major work of philosophy that still has worth in today’s world?

You must be logged in to post a comment.