Probably the ultimate bad ass of the Civil War was Lieutenant General Nathan Bedford Forrest, commander of Confederate cavalry forces operating primarily in Mississippi and his native state of Tennessee. Just to give you an idea of how divisive a figure he has come to be, the above image was hijacked from the website of the Ku Klux Klan, of which Forrest was first Grand Wizard.

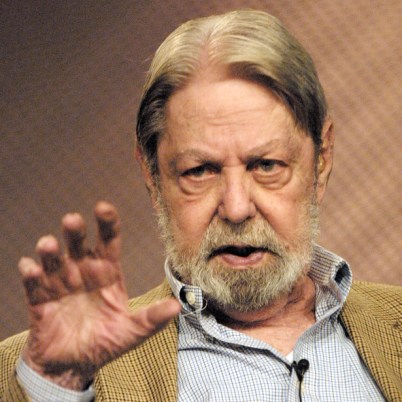

I have just finished reading Jack Hurst’s Nathan Bedford Forrest: A Biography. What is it that interests me about this man? First of all, the late Civil War historian and novelist Shelby Foote referred to him as being one of the two authentic geniuses produced by the conflict. The other was Abraham Lincoln. As William Tecumseh Sherman wrote, he was “the most remarkable man [the war produced, with] a genius for strategy which was original and … to me incomprehensible… He seemed always to know what I was doing or intended to do, while I … could never … form any satisfactory idea of what he was trying to accomplish.”

Forrest used cavalry in a manner that dumfounded his enemy. Instead of attacking on horseback, he used the horses to move his men to battle, whereupon he had them fight on foot as if they were infantry. Once, when attacked on two sides by Union forces, he divided his forces in two and had them attack in both directions. At the Battle of Brice’s Crossroads, which he won against insuperable odds, he made one maneuver which I simply cannot wrap my head around: He attacked with artillery.

One result of his unconventional methods was that he didn’t get along with higher ranking generals with whom he was supposed to cooperate. At one point, he threatened Braxton Bragg to his face. There were numerous other Confederate generals with whom he refused to fight, with the result that, most of the time, he was on his own in territory that he knew well from his childhood.

In the north, he is most famous for the massacre of Fort Pillow in Tennessee, which was mostly manned by black Union forces. When he felt that the negotiations for a truce were being conducted with bad faith (as, indeed, he had some reason to believe), he ordered his men to “kill every God damned one of them.” When he saw the results of his orders, he relented; but not before hundreds of black and white Union soldiers were killed rather than captured. The taint of this action was to haunt him for the rest of his life.

Although he did not found the Ku Klux Klan, Forrest was its first Grand Wizard. After a couple of years, however, he saw where the organization was headed and decided to repudiate it. Instead, he went in for building a railroad between Memphis and Selma, Alabama. The reputation as the perpetrator of the Fort Pillow massacre and his association with the KKK continued to follow him. As he began to suffer bad health, Forrest tried to become a force for good in the South and even became supportive of the African-Americans with whom he dealt, to the extent that hundreds honored him at his funeral when he died of advanced diabetes in 1877.

When it became clear to him that the Southern cause in the Civil War was lost, he addressed his troops:

Civil war, such as you have just passed through, naturally engenders feelings of animosity, hatred, and revenge. It is our duty to divest ourselves of all such feelings, and, as far as in our power to do so, to cultivate friendly feelings toward those with whom we have so long contended…. Neighborhood feuds, personal animosities, and private differences should be blotted out; and, when you return home, a manly, straightforward course of conduct will secure the respect even of your enemies. Whatever your responsibilities may be to the government, to society, or to individuals, meet them like men.

… I have never, on the field of battle, sent you where I was unwilling to go myself; nor would I now advise you to a course which I felt myself unwilling to pursue. You have been good soldiers, you can be good citizens. Obey the laws, preserve your honor, and the government to which you have surrendered can afford to be, and will be, magnanimous.

Today, when the stormy petrel figure of Nathan Bedford Forrest is still being used to divide Americans, it is interesting to see in him a person who changed during his lifetime from a slave dealer in Memphis to a powerful guerrilla fighter to a Klansman and finally to the much-loved warden of a prison farm on an island in the Mississippi where most of his charges were black.

You must be logged in to post a comment.