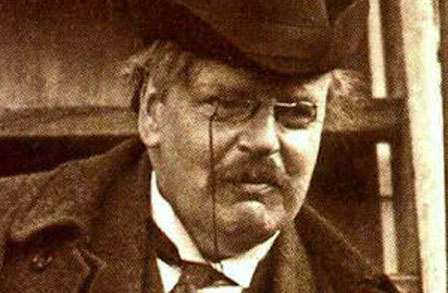

British Writer G. K. Chesterton (1874-1936)

As a voracious reader of books, I have always had my strange little reading traditions. For example, in most years, I have usually read a couple of G. K. Chesterton’s books every February. This year was no different: Since February 1, I have read The Club of Queer Trades (1911) — a re-read, Appreciations and Criticisms of the Works of Charles Dickens (1911), and All I Survey (1933). Below is a quote from his book Orthodoxy (1908) in which he demonstrates, by the following quote, that he knows children as well as he knows God:

Because children have abounding vitality, because they are in spirit fierce and free, therefore they want things repeated and unchanged. They always say, “Do it again”; and the grown-up person does it again until he is nearly dead. For grown-up people are not strong enough to exult in monotony. But perhaps God is strong enough to exult in monotony. It is possible that God says every morning, “Do it again” to the sun; and every evening, “Do it again” to the moon. It may not be automatic necessity that makes all daisies alike; it may be that God makes every daisy separately, but has never got tired of making them. It may be that He has the eternal appetite of infancy; for we have sinned and grown old, and our Father is younger than we.

You must be logged in to post a comment.