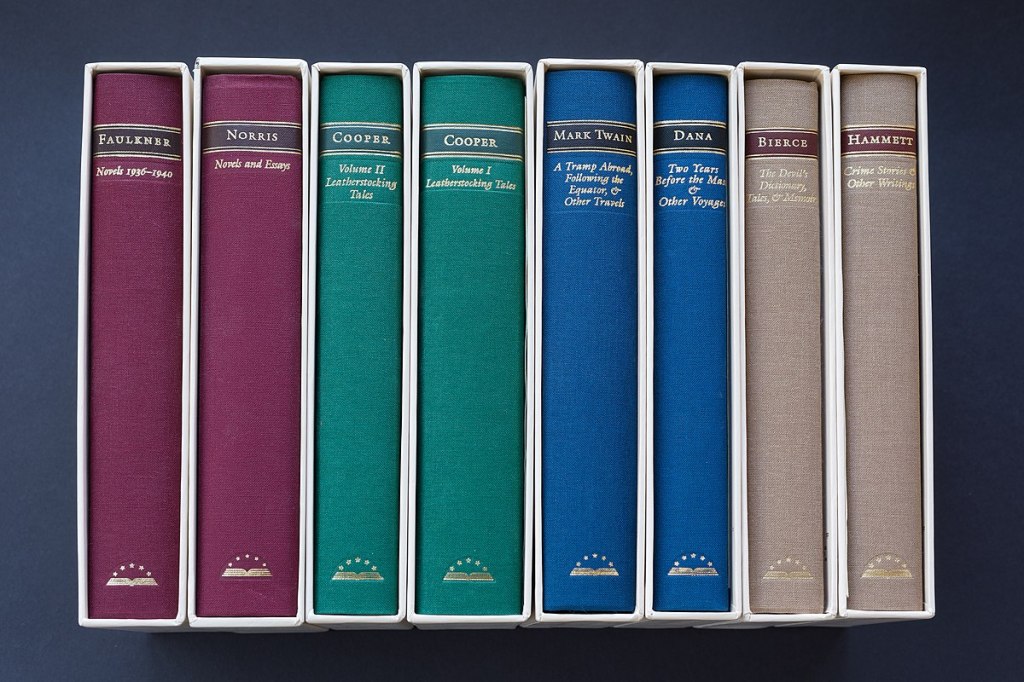

Selected Library of America Volumes

Some forty years ago, I visited my friend Mike Prendergast and saw some intriguing books on his shelf. They were early volumes published by the Library of America. They were slipcased hardbound volumes averaging 800-1000 pages each with authoritative editions of American authors such as Nathaniel Hawthorne, Edgar Allan Poe, Benjamin Franklin, and Herman Melville. The attempt was to do for the United States what the Pléiade editions did for France.

I wasted no time in contacting the L of A, and in no time at all I started receiving all the volumes they published. As the publisher branched out more, I had to cut back considerably. Today, I have more than 200 volumes containing the works of William Faulkner, Mark Twain, Henry James, and scores of other authors.

For a while, I started to look down on American literature and concentrate my reading efforts on European authors. I now realize that was short-sighted, so I started to dig into some of the volumes on my shelves. Among the works I discovered were:

- Dawn Powell (The Locusts Have No King and Turn, Magic Wheel)

- Kenneth Fearing (The Big Clock)

- William Lindsay Gresham (Nightmare Alley)

- Shirley Jackson (The Haunting of Hill House and We Have Always Lived in the Castle)

- Jack Kerouac (The Subterraneans)

- Henry David Thoreau (A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers and The Maine Woods)

- William Faulkner (Soldier’s Pay, Mosquitoes, and A Fable)

- Mark Twain (Following the Equator)

One of my long-term projects is reading all the published works of Joan Didion in order, which was made easier by the L of A publishing her novels and essays in two volumes (The 1960s & 1970s and The 1980s & 1990s). I have no doubt that her later works will appear in a volume to be published.

I am also thinking of reading all of Henry James’s shorter works, including some of the novels I have not yet read, such as The Awkward Age and Wings of the Dove.

There are hundreds of treasures to be found in the Library of America. I can only hope to live long enough to do them justice.

You must be logged in to post a comment.