Auteuil in Paris’s 16th Arrondissement

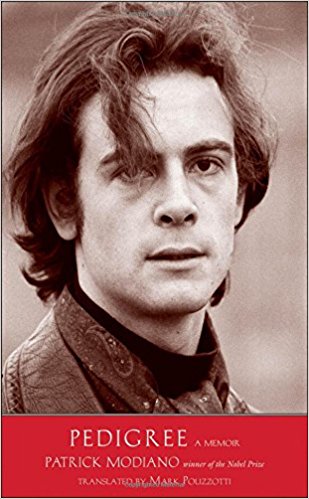

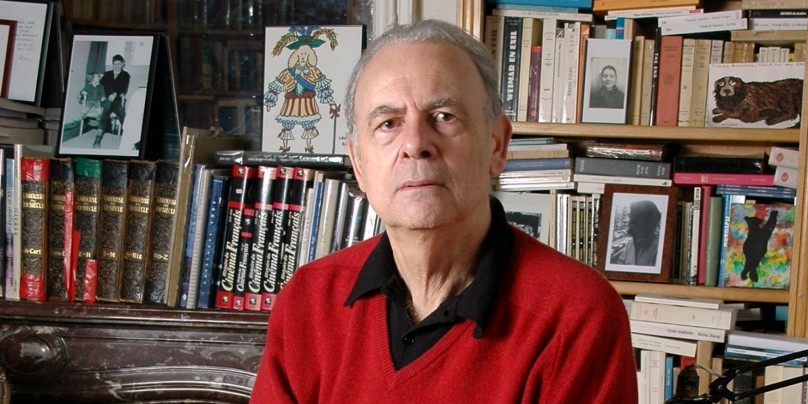

Of recent French authors, the one I am most addicted to is Patrick Modiano, winner of the 2014 Nobel Prize for Literature. Since I first read his Out of the Dark (1998) for an Internet French Literature group ten years ago, I have read most of his work and am still hungry for more, though there are only a few titles left to go. And, no doubt, I will probably start re-reading them.

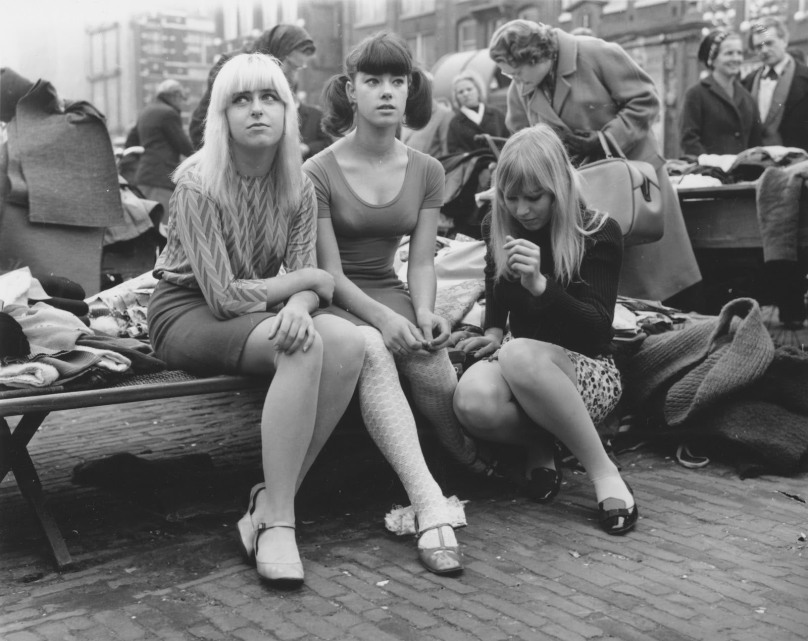

Scene of the Crime (2021) is one of his most recent novels, which I just finished today. Jean Boesman experienced some fascinating but very dicey people back in the 1960s and is haunted by the memory. He has been sought after by several of them for knowing where some swag from past smuggling has been hidden, but he successfully avoids them. Nonetheless, he still endlessly goes over his relationship with the young women in the group. As he says at one point, “We are from our childhood as we are from a country.”

That country was the Paris of the 1960s and 1970s. I cannot read Modiano without a map book of Paris on my lap, following his characters wanderings and evasions through the most walkable city on Earth.

In Scene of the Crime, I tracked Boesman through Boulogne-Billancourt (where Modiano was born), Auteuil, Pigalle/Place Blanche, the Quays along the Seine, and Saint Lazare.

None of Modiano’s books are particularly long: Most can be completed in one or two sittings. I usually take a little longer, because I am following the action on a map of Paris.

You must be logged in to post a comment.