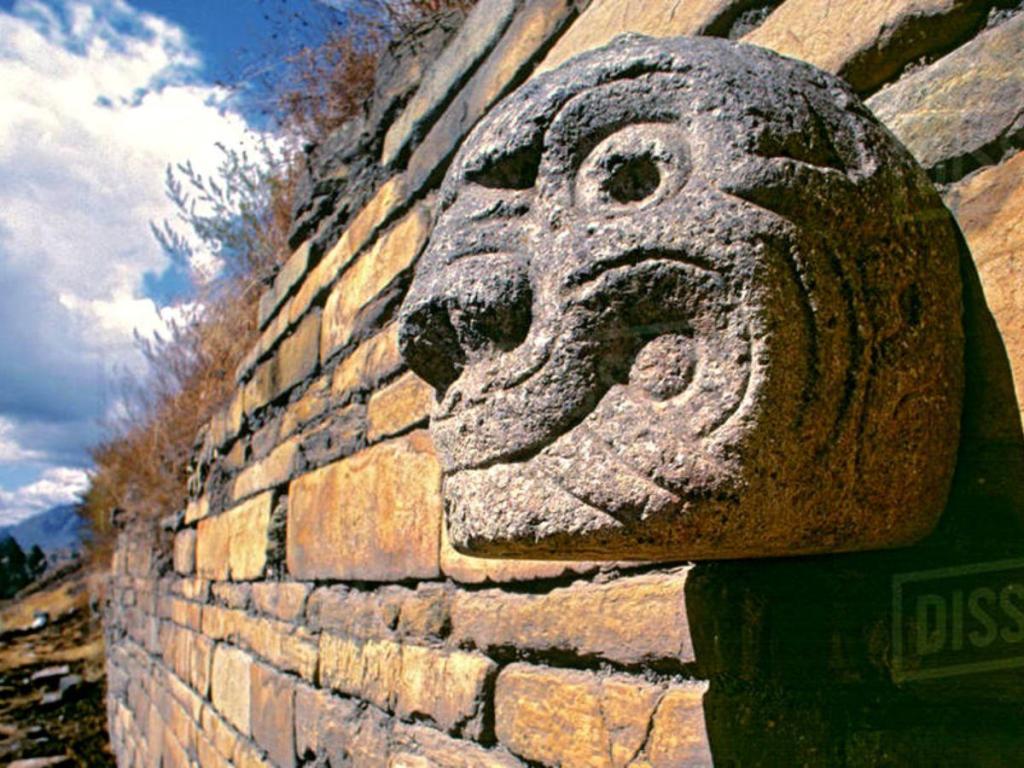

The Citadel at the Chimu Ruins of Chan Chan

I am sketching out here a possible trip to see the non-Inca ruined cities of Northern Peru. Yesterday, I dealt with Huaraz and the ruins of Chavin de Huantar. From Huaraz, it is a seven-hour bus ride back to the Pacific Coast and the colonial city of Trujillo.

Francisco Pizarro founded Trujillo in 1534, naming the city after his birthplace in Spain’s Estremadura. The area had already been inhabited by the Chimu, whose ruined city of Chan Chan covered 20 square kilometers (8 square miles) and was said to be the largest pre-Columbian city in the Americas.

In addition to Chan Chan, there are other nearby archeological sites at Huaca Esmeralda, Huaca Arco Iris, Huaca del Sol, and Huaca de la Luna, to name just a few.

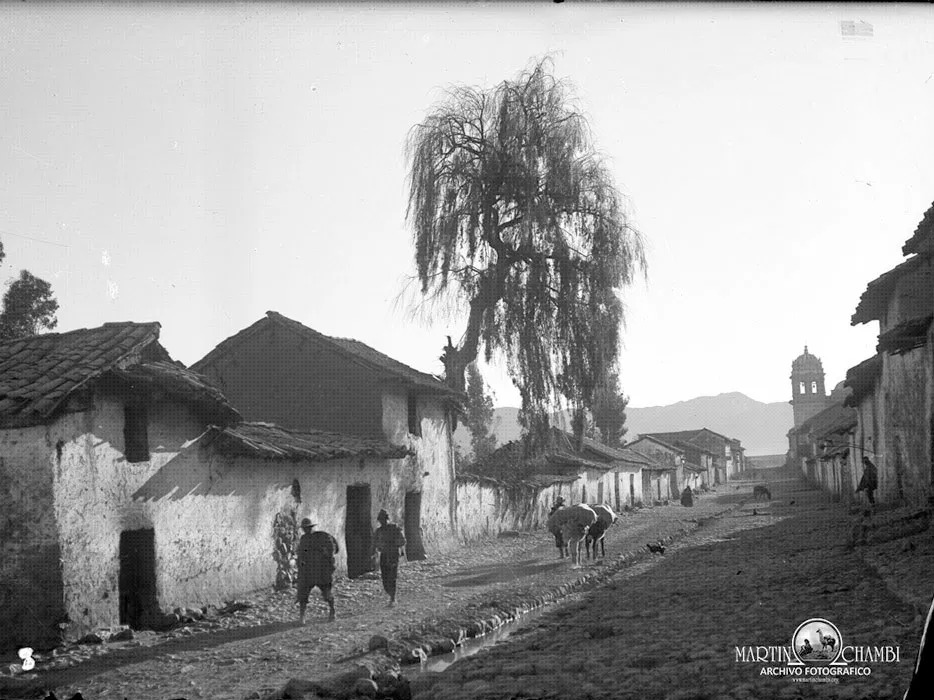

Trujillo would be a good city to base myself in for several days, as there are a number of colonial structures of architectural and historical interest worth seeing. And the restaurants are rumored to be excellent.

Trujillo’s Cathedral and Casa de Urquiaga

The blue structure on the right was where Simon Bolivar had his headquarters in 1824 during his final campaign to liberate Peru from Spanish control. Just east of the Plaza de Armas is the Casa de la Emancipación where Trujillo’s independence from Spanish rule was formally declared in December 1820.

From Trujillo, I would head northeast, back into the mountains, to see Cajamarca and Chachapoyas, which I will describe in my next post.c

You must be logged in to post a comment.