Mention Quantum Theory to a non-scientist, and what you frequently get in response is a look of profound puzzlement. Even Einstein has weighed in against many of its premises by calling it “spooky action at a distance.” Elsewhere, he asserted that “God does not play dice.” I mean, if Einstein wasn’t on board with this, how could it be true?

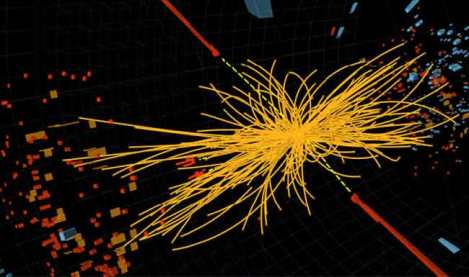

Close to the center of the theory is what is called the Copenhagen Interpretation, proposed by Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg around 1925-1927. According to it, in the world of micro particles, there are no equivalent certainties to the world of big objects like stones, trees, or even planets. If you set up an experiment such as the one illustrated below in which a photon is fired at an opaque object in which two slits are cut, the end result on a receiving surface is not nice and predictable. At times, it will seem that a single photon will go through both slits simultaneously, which would seem to be impossible. At times, when light is shone through the slits, it will seem that the light will act as if it were a particle; other times, it will act as if it were a wave.

Every few years, I read another book on quantum theory to see what physicists are doing with it. Currently, I am reading Through Two Doors at Once: The Elegant Experiment That Captures the Enigma of Our Quantum Reality by Anil Ananthaswamy. Like most books on the subject, there is a heavy reliance on the history of the theory over the last hundred years or so, ending with experiments currently in play.

It’s hard to believe that such a simple experiment could flummox so many incredibly smart people, but it does. And it even still flummoxes me.

You must be logged in to post a comment.