Sam Weller and His Father Tony

Although I first read Charles Dickens’s The Pickwick Papers in the late 1960s, a number of its characters have remained fresh in my memory. Aside from Mr Pickwick himself, there was Sam Weller and his father Tony, Job Trotter, Sergeant Buzfuz, and Angelo Cyrus Bantam. I have always regarded this book as one of Dickens’s best, though I had the feeling in the back of my mind that I would not think so upon re-reading it.

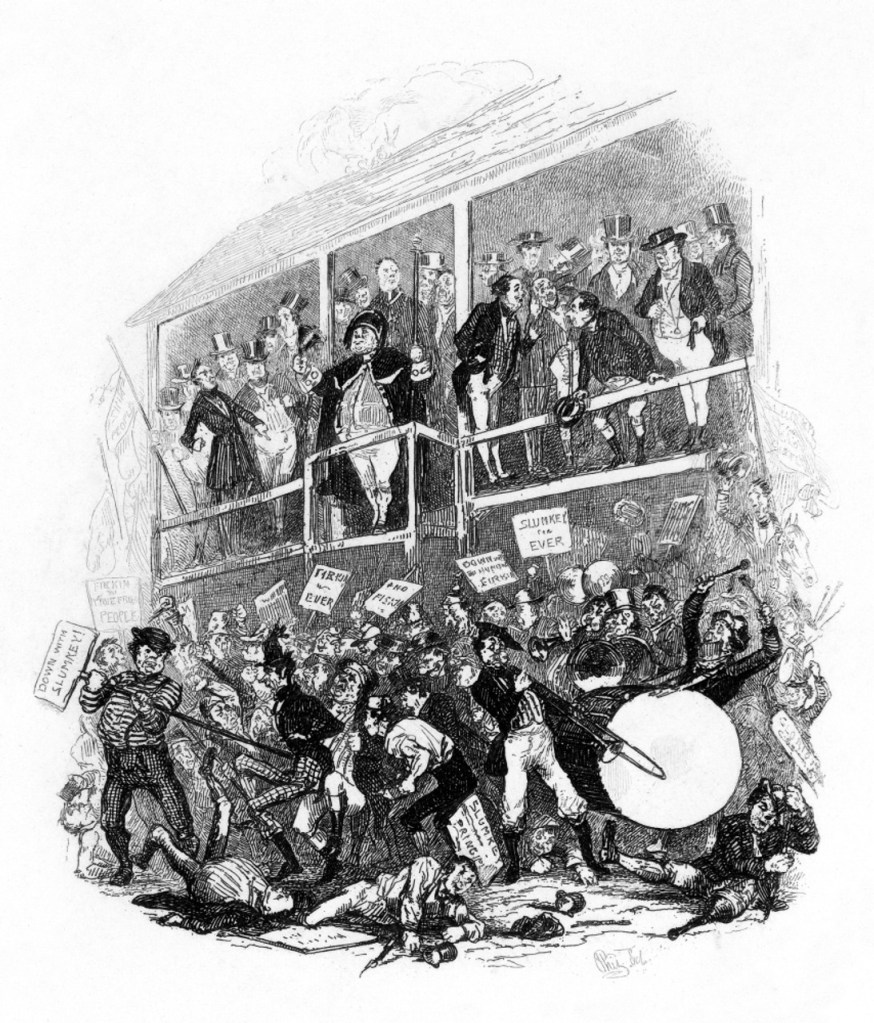

Fortunately, I was wrong. I loved the book—again. It is one of those long picaresque shaggy-dog stories that sags in some places, but rises to incredible heights during such set pieces as the parliamentary election at Eatanswill, the trial of Mr Pickwick for breach of promise, the time spent in the Fleet debtors’ prison, and the Christmas festivities at Dingley Dell.

The book starts slowly with Pickwick and his three associates (Nathaniel Winkle, Augustus Snodgrass, and Tracy Tupman) as the main characters. Before long, however, we find that the real character of interest is Sam Weller, Pickwick’s manservant. Despite coming from the lower classes, his native wit is considerable, and before long he leaves everyone else in the shade. And he is 100% pure English: He almost defines Englishness.

As the book grinds to a halt, Dickens gives us a delirious ending:

Let us leave our old friend in one of those moments of unmixed happiness, of which, if we seek them, there are ever some, to cheer our transitory existence here. There are dark shadows on the earth, but its lights are stronger in the contrast. Some men, like bats or owls, have better eyes for the darkness than for the light. We, who have no such optical powers, are better pleased to take our last parting look at the visionary companions of many solitary hours, when the brief sunshine of the world is blazing full upon them.

In the end, we have been mightily entertained. There has been much humor and—a rarity in Dickens—very little extreme pathos.

Yes, indeed, this is still one of the great books!

You must be logged in to post a comment.