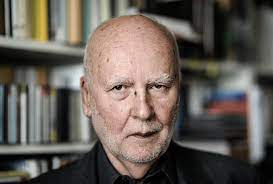

Polish Poet Czeslaw Milosz (1911-2004)

Czeslaw Milosz was born in Eastern Europe the same year as my father was born. Only, Elek Paris was no poet; and Czeslaw Milosz was one of the greatest poetic voices of his century. For many years, he lived in the United States and taught at Berkeley. He won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1980 and died in his native Poland in 2004.

Note that the title of the following poem ends with a question mark:

Ars Poetica?

I have always aspired to a more spacious form

that would be free from the claims of poetry or prose

and would let us understand each other without exposing

the author or reader to sublime agonies.

In the very essence of poetry there is something indecent:

a thing is brought forth which we didn’t know we had in us,

so we blink our eyes, as if a tiger had sprung out

and stood in the light, lashing his tail.

That’s why poetry is rightly said to be dictated by a daimonion,

though it’s an exaggeration to maintain that he must be an angel.

It’s hard to guess where that pride of poets comes from,

when so often they’re put to shame by the disclosure of their frailty.

What reasonable man would like to be a city of demons,

who behave as if they were at home, speak in many tongues,

and who, not satisfied with stealing his lips or hand,

work at changing his destiny for their convenience?

It’s true that what is morbid is highly valued today,

and so you may think that I am only joking

or that I’ve devised just one more means

of praising Art with the help of irony.

There was a time when only wise books were read,

helping us to bear our pain and misery.

This, after all, is not quite the same

as leafing through a thousand works fresh from psychiatric clinics.

And yet the world is different from what it seems to be

And we are other than how we see ourselves in our ravings.

People therefore preserve silent integrity,

thus earning the respect of their relatives and neighbors.

The purpose of poetry is to remind us

how difficult it is to remain just one person,

for our house is open, there are no keys in the doors,

and invisible guests come in and out at will.

What I’m saying here is not, I agree, poetry,

as poems should be written rarely and reluctantly,

under unbearable duress and only with the hope

that good spirits, not evil ones, choose us for their instrument.

You must be logged in to post a comment.