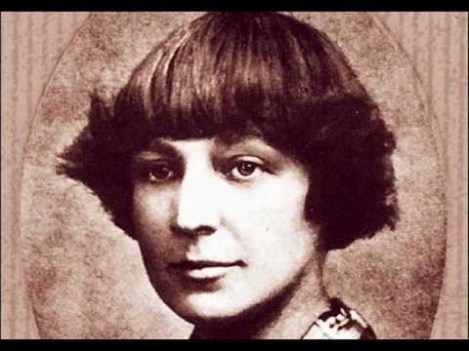

2005 Painting of Marina Tsvetayeva by Aida Lisenkova-Hanemaayer

I have just finished reading Marina Tsvetayeva’s Earthly Signs: Moscow Diaries, 1917-1922 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002). Virtually unknown in the United States, Tsvetayeva was one of the greatest Russian poets of the 20th Century. Here is one of her poems:

I Know the Truth (1915)

I know the truth – forget all other truths!

No need for anyone on earth to struggle.

Look – it is evening, look, it is nearly night:

what will you say, poets, lovers, generals?

The wind is level now, the earth is wet with dew,

the storm of stars in the sky will turn to quiet.

And soon all of us will sleep beneath the earth, we

who never let each other sleep above it.

The above translation is by Elaine Feinstein.

In her Moscow diary, she recounts the experience of being robbed as she leaves a friend’s house late at night:

“Who goes there?”

A young guy about eighteen years old, in uniform, a jaunty forelock peeking out from under his cap. Light brown hair. Freckles.

“Any weapons?”

“What kind of weapons do women have?”

“What is that there?”

”Please, take a look.”

I take out of my purse and hand him, one after the other: my new, favorite cigarette case with lions (yellow, English: Dieu et mon droit), a coin purse, matches.

“And there’s also a comb, a key … If you have any doubts, we can go see the yardkeeper; I’ve lived here for four years.”

“Any documents?”

At this point, remembering the parting words of my cautious friends, I conscientiously and meaninglessly parry:

“And do you have any documents?”

“Right here!”

The steel of a revolver, white in the moonlight. (“So it’s white, and for some reason I always thought it was black.I saw it as black. A revolver—is death. Blackness.”)

At the same instant, the chain from my lorgnette flies over my head, strangling me and catching on my hat. Only then do I realize what’s going on.

“Put down that revolver and take it off with both hands, you’re strangling me.”

“Don’t scream.”

“You can hear how I’m speaking.”

He lowers it, and, no longer strangling me, swiftly and deftly removes the doubled chain. The action with the chain is the last one. I hear “Comrades!” behind my back as my other foot steps through the gate.

(I forgot to say that the whole time we were talking (a minute plus) there were people walking back and forth on the other side of the street.)

The soldier left me: all my rings, the lion brooch, the purse itself, both bracelets, my watch, book, comb, key.

He took: the coin purse with an invalid check for 1000 rubles, the new wonderful cigarette case (there you have it, droit without Dieu!), the chain and lorgnette, the cigarettes.

All in all, if not a fair price—a fraternal one.

The next day, Marina hears the young robber was killed by a church custodian:

They offered to let me go pick out my things. I refused with a shudder. How could I—one of the living (that is—happy, that is—wealthy), go and take from him, the dead, his last loot?! I quake at the very thought of it. One way or the other, I was his last (maybe next to the last!) joy, which he took to the grave with him. You don’t rob the dead.

I will have more to say about Tsvetaeva in a future post.

34.052234

-118.243685

You must be logged in to post a comment.