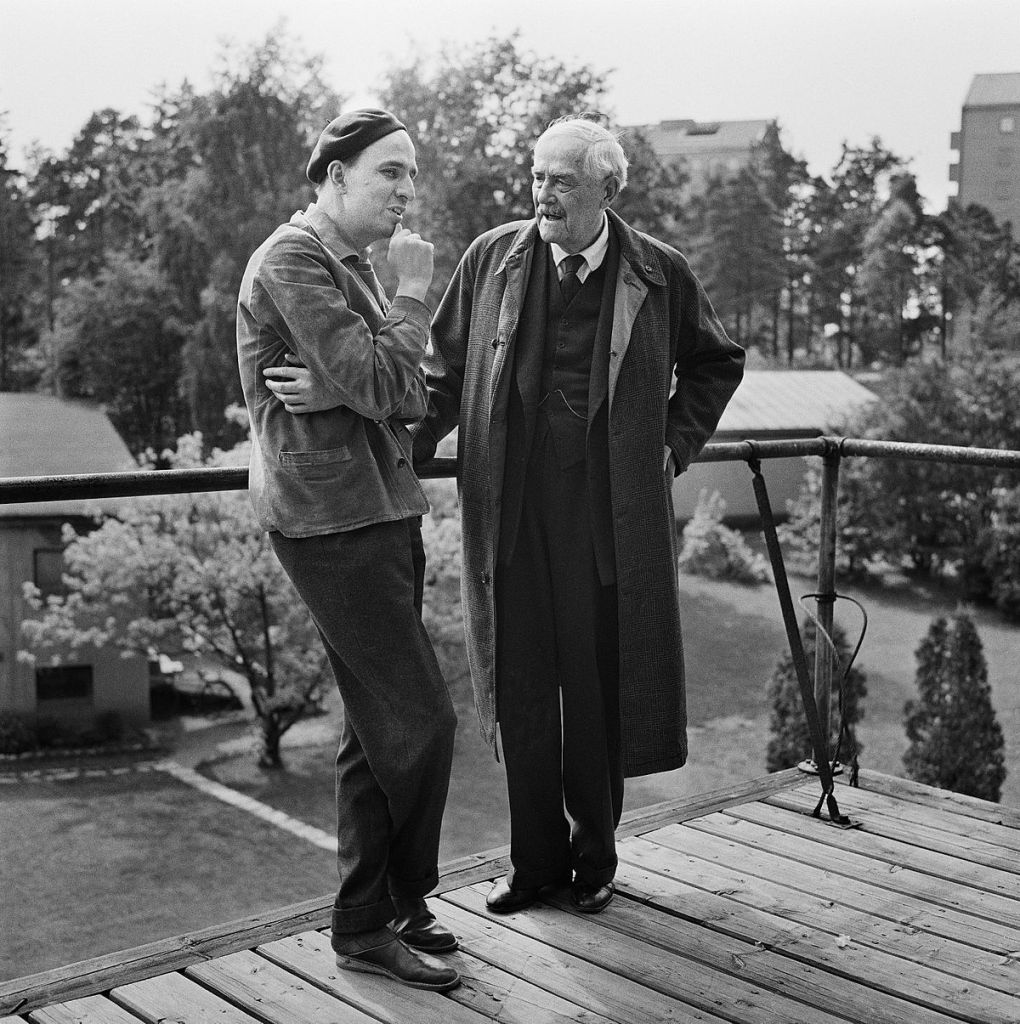

Rieko Yagumo and Yoshiko Tsubouchi in Story of Floating Weeds (1934)

Over the last two days, I have had the good fortune to see two great films by Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu, one the remake of the other. Although the technology to make sound films existed in Japan, Ozu deliberately made only silent films until 1936.

His A Story of Floating Weeds (1934) is about a traveling Kabuki player troupe that visits a small town. On a previous visit to that same town, the head of the troupe, played by Takashi Sakamoto, had an affair with a local woman who ran a small restaurant/bar and had a son by her. In the intervening years, he sent money for his education and begged the mother to say that he was the boy’s uncle instead of his “deceased” father.

Sakamoto loves spending time with his son, and that arouses the envy of Rieko Yagumo, his mistress on the road. She bribes her fellow actress Yoshiko Tsubouchi to seduce the boy, but they fall in love with each other. Furious, Sakamoto dissolves the acting troupe.

Like all of his films, A Story of Floating Weeds shows a group of people at odds with one another coming together in the end with an enhanced respect and gentleness.

It is no surprise that Ozu remade the film in 1959 as Floating Weeds. It is the same basic story, but with sound and color.

The Same Two Roles a Quarter Century Later

I actually prefer the original silent 1934 version. It was a better story and had better actors (even though the 1959 version had Machiko Kyo in the role of the mistress in the troupe). It was so good, in fact, that I plan to buy the recent Criterion release of both versions on DVD.

Yasujiro Ozu was one of the five or ten greatest film directors who ever lived. Over the years, I have seen over a dozen of his films, and there was not a clinker in the bunch. Even John Ford, Jean Renoir, and Carl Dreyer made some stinkers. But not Ozu. The world lost a magnificent artist when he died in Tokyo in 1963. I plan on discussing his film style in a later post this week.

You must be logged in to post a comment.