Lillian Gish in Victor Sjöström’s The Wind (1928)

The title comes from a quote by Gloria Swanson in Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950), after viewing a silent film that starred her:

Still wonderful, isn’t it? And no dialogue. We didn’t need dialogue. We had faces. There just aren’t any faces like that anymore. Maybe one—Garbo. Oh, those idiot producers. Those imbeciles. Haven’t they got any eyes? Have they forgotten what a star looks like? I’ll show them! I’ll be up there again, so help me!

Over the last four days, I have been watching a whole slew of silent films, including both shorts and features, aired by Cinecon from their website at Cinecon.Org.

Originally, I didn’t much care for silent films. They didn’t look sharp on the screen; they were too sentimental; they were too slow; and there were all kinds of problems with the nitrate stock on which they were printed. But I changed my mind, owing primarily to two reasons. First was my friendship with the late John Dorr, who convinced me to give them a second chance. Second was a phenomenal book that came out while I was at UCLA Graduate School, Kevin Brownlow’s The Parades Gone By.

Also, I had the opportunity to see many silent films that were simply phenomenal, and not just fractured flickers. One of them, I just saw a couple of hours ago from Cinecon’s website, Penrod and Sam (1923), directed by William Beaudine for First National Pictures (which morphed into Warner Brothers). It was a gorgeous print, filmed by a director whom I regarded as a nonentity, with no recognizable stars, but so funny withal that my guffaws disturbed Martine, who was napping in the bedroom.

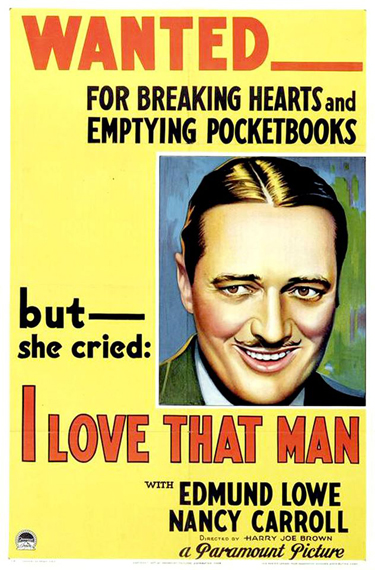

Poster Announcing a Screening of Penrod and Sam

I cannot help but think this film was a major influence on the Our Gang Comedies of the 1930s, which were a major influence on my youth.

Looking back, I think my original feelings about silent films had mostly to do with the hundred or so years that separated me from them. The 1910s and 1920s were a far different time. The population of the country was overwhelmingly white and Protestant. It was, for all intents and purposes, a different America. Now, it no longer bothers me so much viewing these films of a bygone era, one with which I was not altogether in sympathy.

Within a few days, I intend to present a list of the greatest silent films made in the United States, and perhaps follow it up with a similar European list.

You must be logged in to post a comment.