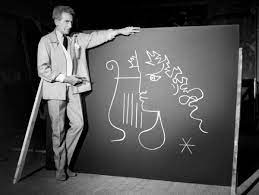

Giorgio di Chirco’s “Gare Montparnasse: The Melancholy of Departure”

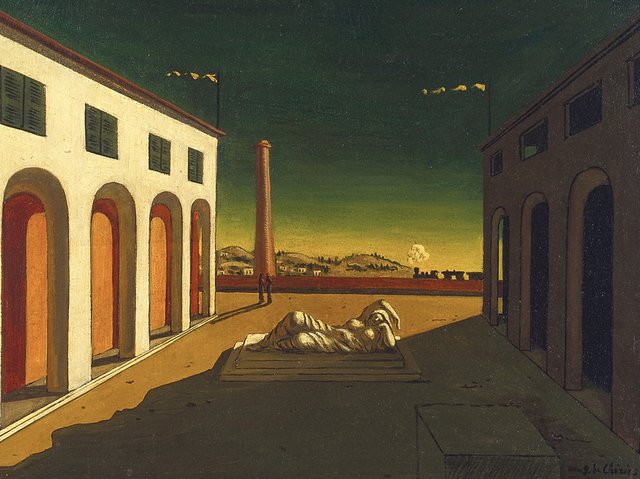

I usually do not write about a book until I have finished reading it, but I decided that I had to post this while the ideas were still fresh in my mind. Geoff Dyer’s novel The Search (1993) started out as a genre mystery/detection novel, but has transformed into a Giorgio di Chirico painting.

We are in a non-specific country in an area known as The Bay. A man named Walker (no first name given) winds up at a party with his brother and meets an alluring woman known as Rachel Malory and asks him to track down er ex-husband in order to get some papers signed. Walker finds Rachel seductive, but she does not allow herself to be seduced, which only spurs Walker on. Although he does it ostensibly for money, it is really she who is the goal of his endeavors.

So far, so good. But it is not long before strange things begin to happen. First of all, he meets a man named Carver who wants badly to compare notes with him about Malory. When he refuses, Carver threatens to kill him. So while he is chasing Mallory, he is being chased by Carver. Then even stranger things begin to happen:

There was something strange about the city but he was unable to work out what. Then it came to him. There were no trees or pigeons or gardens. Yet all around were the sounds of leaves rustling and the beating of wings, the cooing of departed birds. He was so shocked that he stood at a street corner, listening.

Then there was a closed bridge that was actually vibrating like a plate of Jello in the wind. Walker goes through a series of tatty cities in this strange nondescript landscape. In one, there are no people; and he is able to get a suit and a car without paying for them. In another, there doesn’t seem to be much of a city, but whatever there is is surrounded by a network of wide freeways on which all the motorists are speeding furiously.

There don’t seem to be any clues about Malory, but Carver or some unknown assailant is still chasing him through a series of random cities.

“Enigma of a Day”

That’s when I thought of di Chirico, that painter of mysteriously nonspecific cities. Cities like Meridian, Port Ascension, Eagle City, Usfret, Kingston, Monroe, Durban, Iberia, Friendship—the list stretches on. Each town is different from the other, in a sort of alternate United States with black and Latino ghettos. In one unnamed city, he even finds what looks to be a picture of Malory with Rachel.

As the surrealism grows, I almost want to ration the rest of the book so that I don’t finish it too soon.

34.052234

-118.243685

You must be logged in to post a comment.