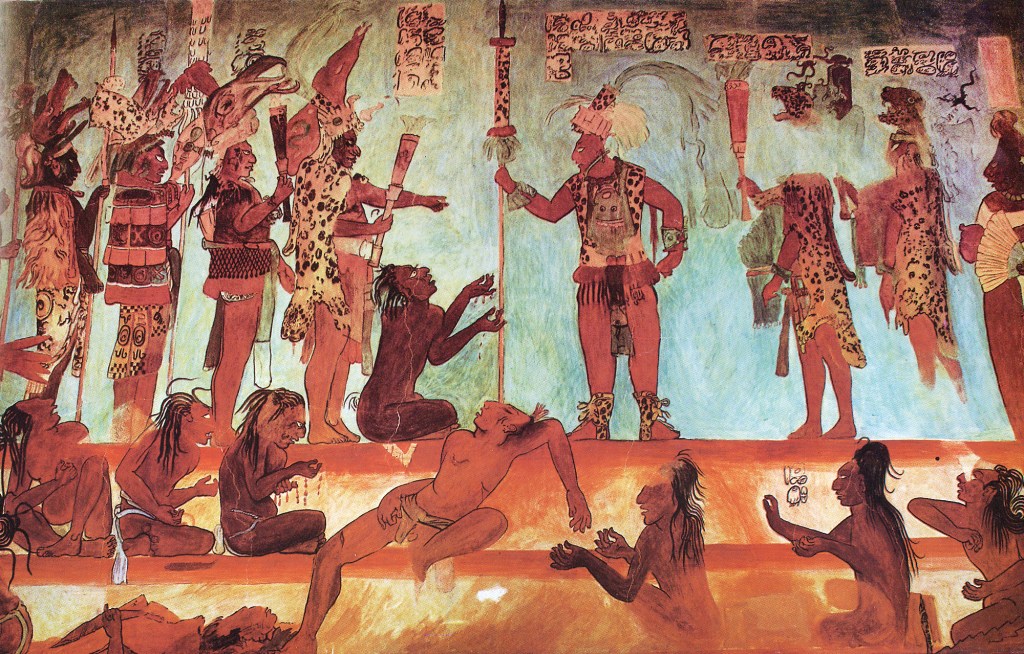

Chinese Soldiers Around Time of Tu Fu (8th Century)

Two of the greatest poets who have ever lived are Li Po and Tu Fu (a.k.a. Du Fu), who not only lived around the same time in China but who knew each other. Here is a heartbreaking poem by Tu Fu about coming back home after the wars to find his home has changed irrevocably.

A Homeless Man’s Departure

After the Rebellion of 755, all was silent wasteland,

gardens and cottages turned to grass and thorns.

My village had over a hundred households,

but the chaotic world scattered them east and west.

No information about the survivors;

the dead are dust and mud.

I, a humble soldier, was defeated in battle.

I ran back home to look for old roads

and walked a long time through the empty lanes.

The sun was thin, the air tragic and dismal.

I met only foxes and raccoons,

their hair on end as they snarled in rage.

Who remains in my neighborhood?

One or two old widows.

A returning bird loves its old branches,

how could I give up this poor nest?

In spring I carry my hoe all alone,

yet still water the land at sunset.

The county governor’s clerk heard I’d returned

and summoned me to practice the war-drum.

This military service won’t take me from my state.

I look around and have no one to worry about.

It’s just me alone and the journey is short,

but I will end up lost if I travel too far.

Since my village has been washed away,

near or far makes no difference.

I will forever feel pain for my long-sick mother.

I abandoned her in this valley five years ago.

She gave birth to me, yet I could not help her.

We cry sour sobs till our lives end.

In my life I have no family to say farewell to,

so how can I be called a human being?

You must be logged in to post a comment.