Once the U.S. abandoned Saigon to the Viet Cong in 1975, we seem to have lost all interest in Southeast Asia. There was, however, a lot happening. The Pol Pot regime in Cambodia, which was supported by the Chinese, was engaged in genocide on a massive scale. Also, we must not forget at that time that the Sino-Soviet conflict was at its height: The Russian-Chinese border fairly bristled with guns and military units. At the time, the Hanoi government had a military alliance with the Soviet Union. When Vietnam invaded Cambodia and deposed the Khmer Rouge, China decided to punish its neighbor to the south.

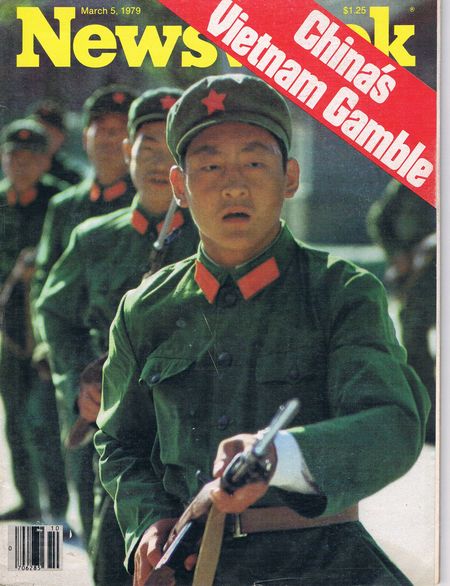

On February 17, 1979, somewhere between 200,000 and 600,000 troops of the Peoples’ Liberation Army (PLA) invaded North Vietnam and occupied the all territory for approximately twenty miles south of the border. It appears that China either wanted to test the alliance with Russia or divert the crack Viet military units engaged in Cambodia—or both, or neither. A number of reasons have been adduced for this incursion, and China wasn’t owning up to its motivation for so doing. Vietnam met the attack by the 1st and 2nd military regions—essentially militia—under the command of Dam Quang Trung and Vu Lap. The number engaged of the Vietnamese forces was a fraction of the Chinese force, but it inflicted heavy casualties on the PLA, and suffered heavy casualties in return. (The numbers vary depending on whether one is following Chinese or Vietnamese statistics.)

When I heard that, after thirty-five years of relative peace, the Chinese are once again testing the resolve of the Vietnamese by drilling an oil well off the Paracel Islands in the South China Sea, which are claimed by both nations, my antennae started to tingle. Tiny uninhabited islands are big news these days, mainly because they extend the territories claimed by adjoining land powers. Claiming a tiny rock can extend one’s territorial waters by literally thousands of square miles. And both China and Vietnam need all the oil they can get.

The Vietnamese responded by rioting and attacking Chinese within their borders, along with the businesses they ran. China has been chartering flights to evacuate its nationals from Vietnam.

Although the PLA is huge, it is largely untested in battle. The Sino-Vietnamese War of 1979 was probably the largest military conflict it faced in the last half century—and it did not fare too well faced with a smaller number of Vietnamese militia. At that time, one must remember that the Vietnamese had been at war ever since the end of World War Two and, as a people, were probably as battle-hardened as one could be.

It would be interesting to see whether China is willing, once again, to test Vietnam’s resolve.

You must be logged in to post a comment.