ancient The photo above is of a contemporary figurine of a Pre-Columbian idol on display in Quito’s Museo Mindalae. Although I doubt there was much trade between the ancient peoples of Ecuador and the Olmecs, Maya, and Aztecs of Mexico, there are clearly similarities in their religious iconography.

Before I began my travels to Latin America in 1975, I was puzzled by the images I saw of deities and demons from the more civilized portions of Meso-America. There were many similarities. But once one crossed the Rio Grande and visited where the Anasazi lived, the imagery is altogether different. And when I traveled in Argentina, Uruguay, and Chile, I saw precious little suggesting an advanced ancient civilization (though, in all honesty, I never visited the Northwest of Argentina, which was part of the Inca empire).

Now look at the depiction of one of the Mayan Priest Kings of Yucatán from the Mérida Museum of Anthropology:

Note the elaborate headdress and the warlike demeanor. Do not expect mercy from either of these rigidly powerful figures. I remember a conversation that took place at a symposium at UCLA decades ago between two archeologists, Michael Coe and Nigel Davies, about whether they would prefer to be in captivity to the Mayans or the Aztecs. Both agreed that, although the Aztecs were an empire and the Mayans were a group of city states, they both feared being prisoners of the Maya.

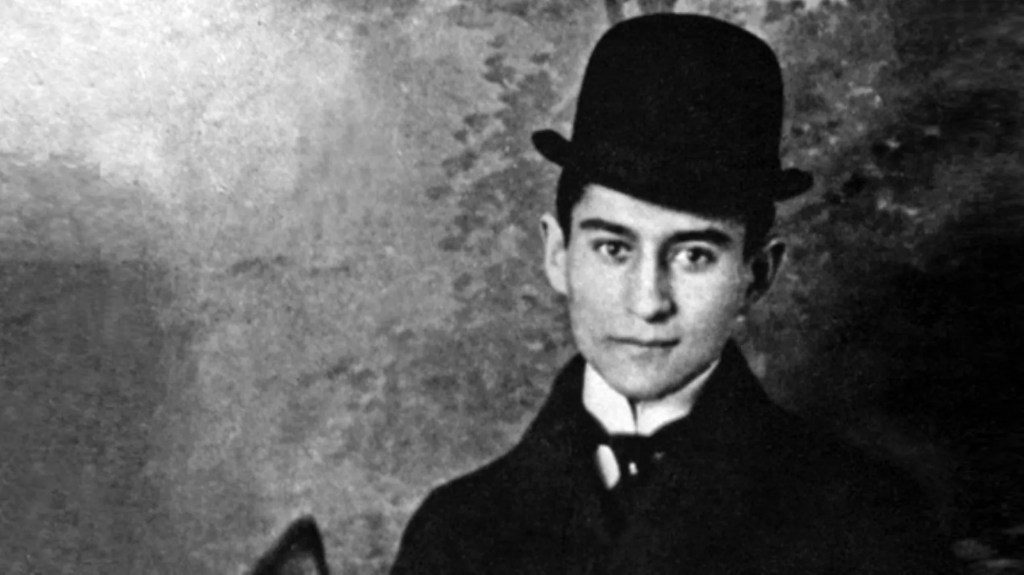

Why? Take a look at this fresco from the ruins at Bonampak in Chiapas:

Here you see the victorious Maya of Bonampak with their prisoners captured in a war with another city state. The scene is described in the Sixth Edition of Robert J. Sharer’s The Ancient Maya:

The aftermath is presented on the north wall. Here the full-frontal figure holding his jaguar-pelted spear, again probably Chan Muwan, accompanied by his warrior allies and entourage, along with two women at the far right, stands on the summit of a platform to preside over the captives taken in the battle. The chief captive sits at Chan Muwan’s feet, while the rest of the unfortunate prisoners are displayed on the six steps of the platform, where they are tortured and bled from their fingernails, held and guarded by more victorious warriors. These are the captives that will be sacrificed; one sprawled figure may already be dead, and the severed head of another has already been placed on the steps.

What all these Meso-American peoples had in common was highly organized and ritualistic warfare. Reading the history of many of these city states based on commemorative stelae, paintings, and other media, one clearly gets the feeling that life for the common people was anything but fun.

You must be logged in to post a comment.