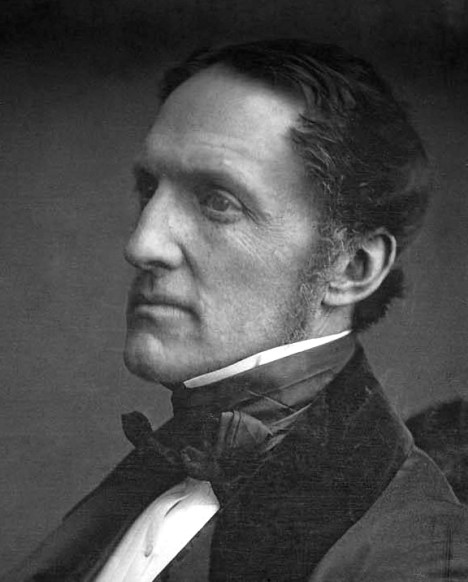

William H. Prescott (1796-1859)

It all started with a food fight in the Harvard University dining hall, or commons. A not particularly distinguished student from a famous family, William Hickling Prescott was hit in the left eye with a crust of bread. The impact destroyed the vision of his left eye for life and, in fact, knocked him out. The trouble began when he started suffering degeneration in his right eye. During his youth, there were whole months at a time when Prescott was blind and had to stay in a darkened room.

But things got better. By then, Prescott went to Europe and fell in love with the history of Spain. He wrote The History of the Reign of Ferdinand and Isabella (1837), followed by The History of the Conquest of Mexico (1843) and The History of the Conquest of Peru (1847). During his most productive years, there were still times when he was unable to read or even see. Using the help of secretaries and a device called a noctograph, which enabled him to write clearly in total darkness, Prescott managed to write some of the greatest works of history published in the nineteenth century. In his Preface to The Conquest of Peru, he wrote:

While at the University, I received an injury in one of my eyes, which deprived me of the sight of it. The other, soon after, was attacked by inflammation so severely, that, for some time, I lost the sight of that also; and though it was subsequently restored, the organ was so much disordered as to remain permanently debilitated, while twice in my life, since, I have been deprived of the use of it for all purposes of reading and writing, for several years together. It was during one of these periods that I received from Madrid the materials for the “History of Ferdinand and Isabella,” and in my disabled condition, with my Transatlantic treasures lying around me, I was like one pining from hunger in the midst of abundance. In this state, I resolved to make the ear, if possible, do the work of the eye. I procured the services of a secretary, who read to me the various authorities; and in time I became so far familiar with the sounds of the different foreign languages (to some of which, indeed, I had been previously accustomed by a residence abroad), that I could comprehend his reading without much difficulty. As the reader proceeded, I dictated copious notes; and, when these had swelled to a considerable amount, they were read to me repeatedly, till I had mastered their contents sufficiently for the purposes of composition. The same notes furnished an easy means of reference to sustain the text.

Still another difficulty occurred, in the mechanical labor of writing, which I found a severe trial to the eye. This was remedied by means of a writing-case, such as is used by the blind, which enabled me to commit my thoughts to paper without the aid of sight, serving me equally well in the dark as in the light. The characters thus formed made a near approach to hieroglyphics; but my secretary became expert in the art of deciphering, and a fair copy—with a liberal allowance for unavoidable blunders—was transcribed for the ‘use of the printer. I have described the process with more minuteness, as some curiosity has been repeatedly expressed in reference to my modus operandi under my privations, and the knowledge of it may be of some assistance to others in similar circumstances.

Though I was encouraged by the sensible progress of my work, it was necessarily slow. But in time the tendency to inflammation diminished, and the strength of the eye was confirmed more and more. It was at length so far restored, that I could read for several hours of the day though my labors in this way necessarily terminated with the daylight. Nor could I ever dispense with the services of a secretary, or with the writing-case; for, contrary to the usual experience, I have found writing a severer trial to the eye than reading,—a remark, however, which does not apply to the reading of manuscript; and to enable myself therefore, to revise my composition more carefully, I caused a copy of the “History of Ferdinand and Isabella” to be printed for my own inspection, before it was sent to the press for publication. Such as I have described was the improved state of my health during the preparation of the “Conquest of Mexico”; and, satisfied with being raised so nearly to a level with the rest of my species, I scarcely envied the superior good fortune of those who could prolong their studies into the evening, and the later hours of the night.

But a change has again taken place during the last two years. The sight of my eye has become gradually dimmed, while the sensibility of the nerve has been so far increased, that for several weeks of the last year I have not opened a volume, and through the whole time I have not had the use of it, on an average, for more than an hour a day. Nor can I cheer myself with the delusive expectation, that, impaired as the organ has become, from having been tasked, probably, beyond its strength, it can ever renew its youth, or be of much service to me hereafter in my literary researches. Whether I shall have the heart to enter, as I had proposed, on a new and more extensive field of historical labor, with these impediments, I cannot say. Perhaps long habit, and a natural desire to follow up the career which I have so long pursued, may make this, in a manner, necessary, as my past experience has already proved that it is practicable.

It is with some frustration that I note that Prescott and his great contemporaries, Francis Parkman (The Oregon Trail, The French in North America) and John Lothrop Motley (The Rise of the Dutch Republic) are virtually ignored today—despite the fact that their literary histories are on a par with the best. That he was able to accomplish so much with his vision problems is a miracle. In fact, his histories in general are a miracle.

In preparation for an eventual visit to Peru, I am now reading The History of the Conquest of Peru and marvelling at its author’s insightfulness and sparkling literary style.

You must be logged in to post a comment.