My father was a semi-professional athlete both in Czechoslovakia and in Cleveland, where he played in the 1930s in a nationality-based soccer league. As his firstborn, I was something of a disappointment to him. I was a bit of a shrimp, later ballooning into a short tubby boy with a broad spectrum of allergies. Plus, around the age of ten, I started getting severe frontal headaches almost daily that were constantly misdiagnosed by the physicians we saw. (It turned out to be a pituitary tumor, which was successfully operated on after I graduated from college.)

What unpromising material!

When my brother was born, my father must have breathed a sigh of relief. Dan was tall and an athlete in my father’s mold.

Where did that leave me?

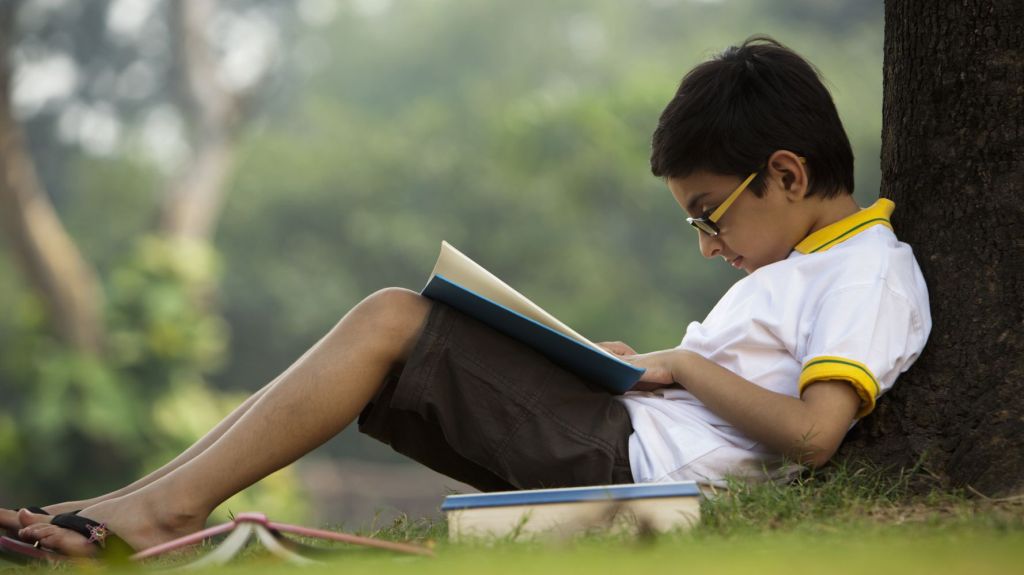

Thanks to my mother’s genius for story-telling—what with dark forests and witches and princesses—I turned to books as soon as I learned to read. There was a period of adjustment of several years during which I had to switch from being an American kid who spoke only Hungarian to an English-speaker. Those dark forests and witches and princesses, luckily, could also be found in books, together with a lot of other interesting stuff.

Although I always had friends, I was left out of school sports because I was frankly somewhat sickly. That turned out to be all right in the end, as my friends were interested in the same sort of things that I was. With Richard Nelson, who was an astronomy freak, I collaborated in writing an illustrated hand-printed study of our solar system and galaxy. Richard later became a meteorologist. Then there was James Anthony, who became a gynecologist.

While I was physically weak, books made me strong in every other way. I never became a famous author or a college professor, but I held down some interesting jobs that help finance my love of books. And I always read a lot. Even today, as I approach my ninth decade, I read anywhere from twelve to sixteen books a month.

What started out as a survival mechanism has brought happiness to my life. I have no children (because I no longer have a pituitary gland), but my retirement years have been mostly contented.

I know that there will be bad times to come as Martine and I age, but I retain a mostly sunny view of life. And in an election year in which Donald Trump is running, that’s a major accomplishment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.