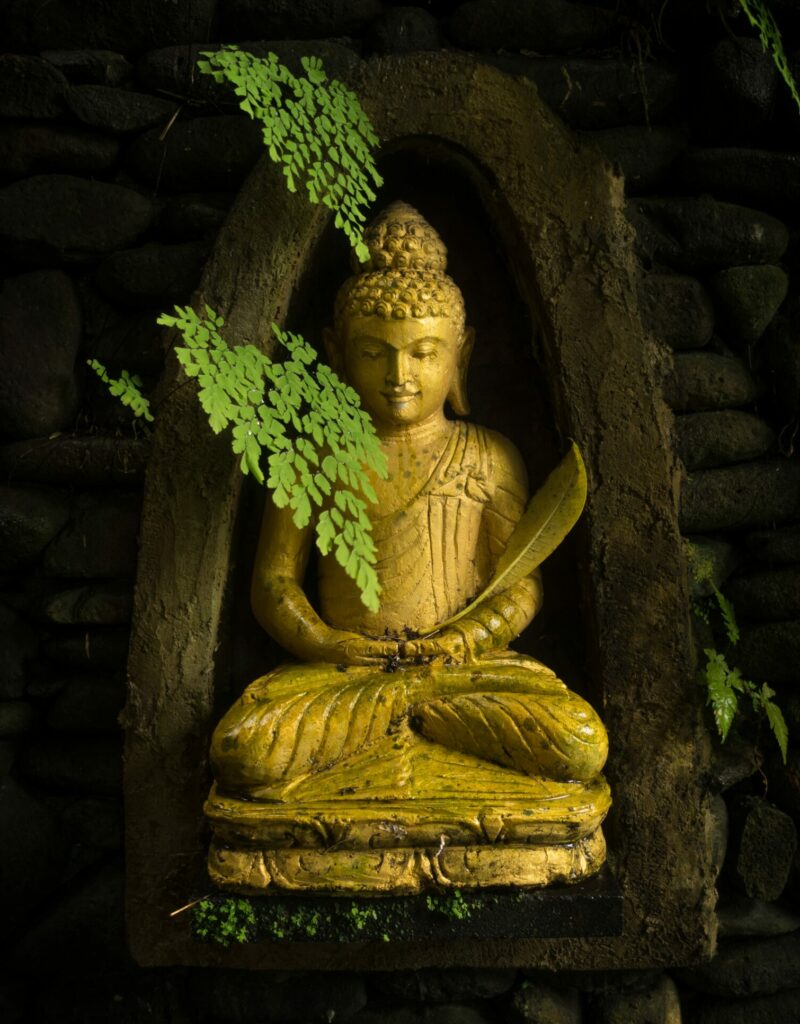

I am currently reading one of the Buddhist scriptures in its entirety, written in the Pali language as The Questions of King Milinda somewhere between 100 BCE and 200 CE. The book’s description of meditation caught my eye:

The king said: “What, Nâgasea, is the characteristic mark of meditation?”

“Being the leader, O king. All good qualities have meditation as their chief, they incline to it, lead up towards it, are as so many slopes up the side of the mountain of meditation.”

“Give me an illustration.”

“As all the rafters of the roof of a house, O king, go up to the apex, slope towards it, are joined on together at it, and the apex is acknowledged to be the top of all; so is the habit of meditation in its relation to other good qualities.”

“Give me a further illustration.”

“It is like a king, your Majesty, when he goes down to battle with his army in its fourfold array. The whole army—elephants, cavalry, war chariots, and bowmen—would have him as their chief, their lines would incline towards him, lead up to him, they would be so many mountain slopes, one above another, with him as their summit, round him they would all be ranged. And it has been said, O king, by the Blessed One: ‘Cultivate in yourself, O Bhikkus, the habit of meditation. He who is established therein knows things as they really are.’”

“Well put, Nâgasena!”

You must be logged in to post a comment.