Antigua Is Surrounded on All Sides by Volcanoes

Antigua, Guatemala was the fourth capital of Guatemala, the other three being destroyed by earthquakes, landslides, and volcanic eruptions. Then, in the eighteenth century, it was Antigua’s turn to succumb. Today, the capital is Guatemala City.

Although it is full of picturesque ruins, Antigua is a more popular destination than the capital. (Also, it is a lot safer.) In fact, there are several shuttle services that will whisk you to Antigua from the Guatemala City airport.

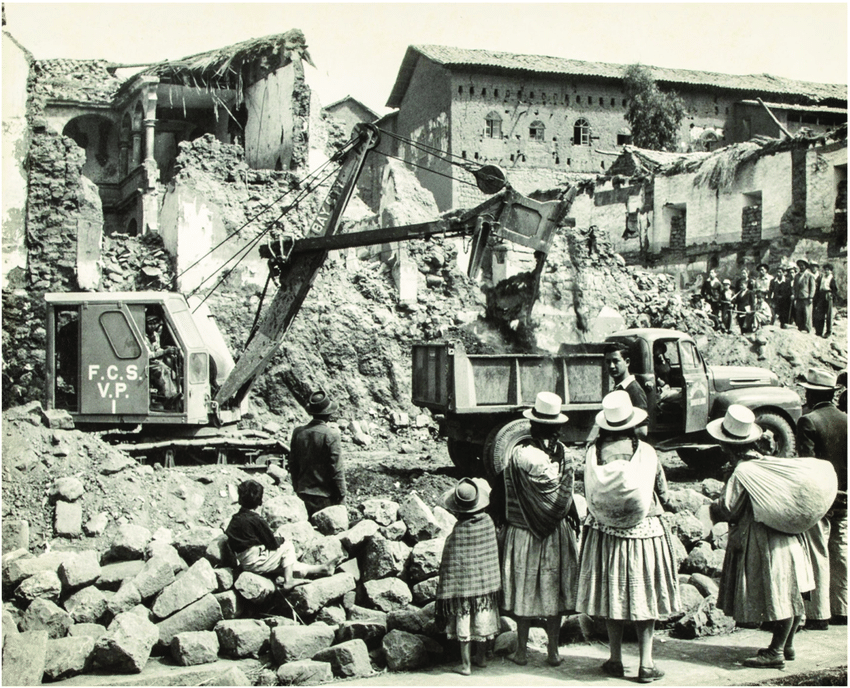

One of the Ruined Churches of Antigua

Antigua was once a city of many churches. Today, most of them are in ruins. Surprisingly, they have become tourist attractions. An attempt was made to clear some of the most dangerous debris. What was left was frequently picturesque and even photogenic.

I was in Antigua for almost a week in 2019. That gave me time to visit most of the ruined churches and take pictures.

One of the Most Damaged Churches in Antigua

I frequently wondered why the churches built by the Spanish were so damaged. My guess is that Spain has not seen that many serious earthquakes; and I suspect there are no active volcanoes on the Iberian Peninsula. The resident Maya, on the other hand, were used to earthquakes and volcanoes; so they built their ceremonial centers to last. The step pyramids of the Maya were built to last. In this respect, the Spanish conquerors had a lot to learn from their “primitive” Maya tenants.

My vacation in Guatemala lasted almost a month, so I was able to see most of the sights that interested me, including the Maya ruins at Tikal and Quiriguá. I even stepped across the border into Honduras to see the ruins at Copán.

You must be logged in to post a comment.