Faiyum Mummy Portrait of a Woman in Her Prime

It is becoming a Black Friday tradition for Martine and I to go to—no, not a shopping center!—but the Getty Villa Museum in Pacific Palisades to view their Greek and Roman antiquities.

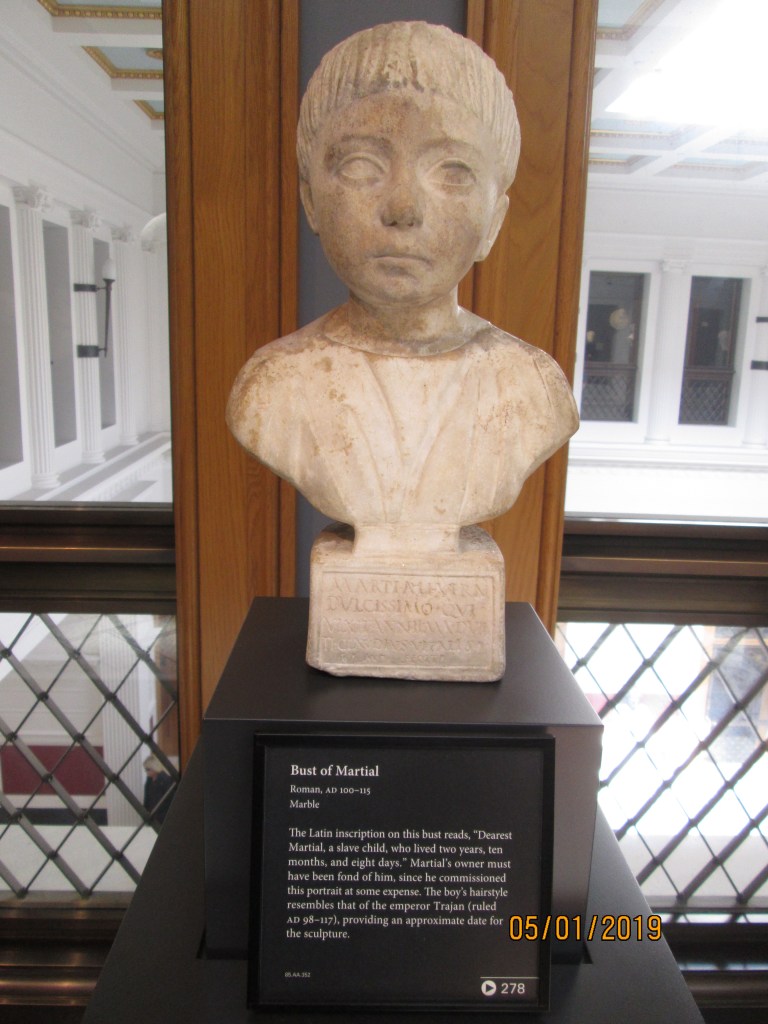

I have always been drawn to the late Egyptian mummies from around A.D. 200, roughly the period of Rome’s Antonine, or so-called “good”, emperors. There was an active Greek community at the time in Alexandria and other coastal areas near the mouth of the Nile, mostly consisting of civilian and military officials. Some were Pagan, others Coptic Christian. Especially around Faiyum, hundreds of mummies were found with painted portraits of the deceased. Strangely, most of them died in their childhood, youth, or the prime of their life. (C.A.T. scans of mummies found with intact painted portraits showed that the age of the body corresponded with the age of the painting.)

Below is an epitaph of one Krokodeilos, who died during this period:

O traveller, stop by me, and learn well who I was:

Besarion’s most loved son, by name Krokodeilos,

But two and twenty summers was my whole life’s span.

Entombed my body lies, beneath a mass of sand,

But my soul’s gone heav’nwards, to Oblivion’s land.

Some day all mortal men in Hades must reside;

This thought brings comfort to the shades of those who’ve died.

Mummy Portrait of a Young Man

At the time these paintings were made, there was very little wall painting being done; whereas the art of mummy portraits was a highly regarded profession. Many of these mummy face paintings have survived with rich coloration intact. Since the Greeks constituted the upper classes of the communities in which they lived, they could usually well afford to commemorate their dead in this way.

The only question I have is: Why did they not produce face paintings for the dead who passed away at an elderly age?

34.052234

-118.243685

You must be logged in to post a comment.