I do not have anything to say about Proust in this posting. Maybe I should have called it “You Can’t Go Home Again” or some such title. My earliest memories are about being raised in a Hungarian household in Cleveland by loving parents. I could not, would not ever repudiate that part of me; and I keep going in search of experiences that, like Proust’s madeleine bring back the happy memories of my childhood.

There used to be some good Hungarian restaurants in Los Angeles; but, as big a city as this is, there do not appear to be any at this time. So Martine and I show up at the local Hungarian Reformed Churches for their festivals. I go to recover my memories, and Martine goes because (although she is French) she loves Hungarian food more than any other.

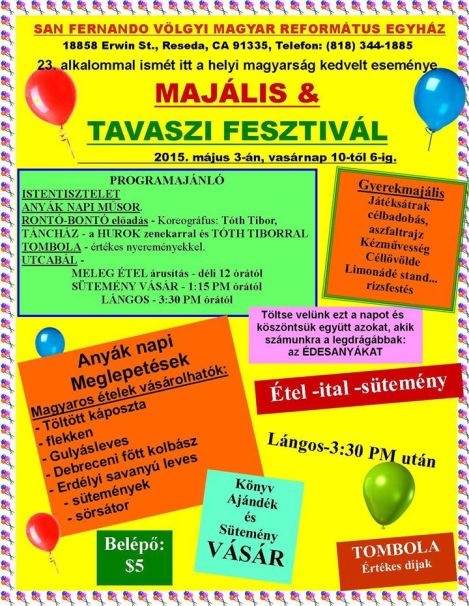

Despite a rare May rain shower, we went to the Majális festival at the Grace Hungarian Reformed Church in Reseda. We have been going here for almost ten years. Even within that short time, we have seen the parishioner base age as the old Hungarians die off and the younger ones spread out to the four winds. Still, the food is excellent. Their stuffed cabbage is superb, and their baked goods are world class.

Their pastor is still Zsolt Jakabffy, who keeps soldiering away at maintaining a parish amid the rapidly changing demographics of the San Fernando Valley.

Wait a minute! What’s a Catholic boy like me doing hanging out at a Protestant church? It all goes back to when my Catholic father and my Protestant Reformatus mother made before their children were born. Any boys would be brought up as Catholic; any girls, as Protestant. Just my mother’s luck that she gave birth to two sons.

So, yes, I have no compunction looking for God wherever He is invoked.

You must be logged in to post a comment.