Here is the best solitary company in the world, and in this particular chiefly excelling any other, that in my study I am sure to converse with none but wise men; but abroad it is impossible for me to avoid the society of fools. What an advantage have I, by this good fellowship, that, besides the help which I receive from hence, in reference to my life after this life, I can enjoy the life of so many ages before I lived! — that I can be acquainted with the passages of three or four thousand years ago, as if they were the weekly occurrences! Here, without travelling so far as Endor, I can call up the ablest spirits of those times, the learnedest philosophers, the wisest counsellors, the greatest generals, and make them serviceable to me. I can make bold with the best jewels they have in their treasury, with the same freedom that the Israelites borrowed of the Egyptians, and, without suspicion of felony, make use of them as mine own. I can here, without trespassing, go into their vineyards and not only eat my fill of their grapes for my pleasure, but put up as much as I will in my vessel, and store it up for my profit and advantage.—William Waller, Divine Meditations: Meditation Upon the Contentment I Have in My Books and Study

Home » Posts tagged 'laudator-temporis-acti' (Page 2)

Tag Archives: laudator-temporis-acti

Books To Be Buried With

I see they packed the volume of Shakespeare that he had near him when he died in a little tin box and buried it with him. If they had to bury it they should have either not packed it at all, or, at the least, in a box of silver-gilt. But his friends should have taken it out of the bed when they saw the end was near. It was not necessary to emphasize the fact that the ruling passion for posing was strong with him in death. If I am reading, say, Ally Sloper’s Half Holiday up to my last conscious hours, I trust my friends will take it out and put it in the waste-paper basket when they see I have no further use for it. If, however, they insist on burying it with me, say in an an old sardine-box, let them do it at their own risk, and may God remember it against them in that day.—Samuel Butler, Notebooks

On Being Always Right

[H]aving lived long, I have experienced many instances of being obliged, by better information or fuller consideration, to change opinions, even on important subjects, which I once thought right, but found to be otherwise. It is therefore that, the older I grow, the more apt I am to doubt my own judgment, and to pay more respect to the judgment of others. Most men, indeed, as well as most sects in religion, think themselves in possession of all truth, and that wherever others differ from them, it is so far error. Steele, a Protestant, in a dedication, tells the Pope, that the only difference between our churches, in their opinions of the certainty of their doctrines, is, ‘the Church of Rome is infallible, and the Church of England is never in the wrong.’ But though many private persons think almost as highly of their own infallibility as of that of their sect, few express it so naturally as a certain French lady, who, in a dispute with her sister, said, ‘I don’t know how it happens, sister, but I meet with nobody but myself that is always in the right — il n’y a que moi qui a toujours raison.’—Benjamin Franklin, speech to the Constitutional Convention (September 17, 1787), in Debates on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution in the Convention Held at Philadelphia in 1787

Either Way Is Okay

It is a series of low buildings among trees. Space in a shrine is horizontal and not, as in a cathedral, vertical. In a church, space is confined. It must struggle upward, having no place else to go. In a shrine, space is spread. There are no high walls, no tight enclosures. The space is a grove and this grove seems so endless that it might be the world itself.

The sky seems low, near. There are long expanses of lawn or grove among the buildings. One is not enclosed, nor is one directed. One is liberated, and almost always alone.

Shrine prayer, as I have said, is not communal prayer. It is solitary prayer. It is not a state—it is a function. It lasts only a minute or so and it is spontaneous. One does not enter, as in churches, or descend, as in mosques. The way to the shrine is through a grove, along a walk, through nature itself, nature intensified. Through these trees, over this moss, one wanders to shrines.

This casual, unremarked acceptance of nature speaks to something very deep within us. It speaks directly to our own nature, more and more buried in this artificial and inhuman century. Shinto speaks to us, to something in us which is deep, and permanent.

Certainly we feel—which is to say, recognize—more here than in smiling Buddhism with its hopeful despair, more than in fierce man-made Islam with its heavenly palaces on earth, more than in the strange and worldly tabernacles of the Hebrews or in the confident, vaunting, expectant Christian churches.

This religion, Shinto, is the only one that neither teaches nor attempts to convert. It simply exists, and if the pious come, that is good, and if they do not, then that too is good, for this is a natural religion and nature is profoundly indifferent.—Donald Richie, The Inland Sea

Learning Armenian

By way of divertissement, I am studying daily, at an Armenian monastery, the Armenian language. I found that my mind wanted something craggy to break upon; and this—as the most difficult thing I could discover here for an amusement—I have chosen, to torture me into attention. It is a rich language, however, and would amply repay any one the trouble of learning it. I try, and shall go on;—but I answer for nothing, least of all for my intentions or my success. There are some very curious MSS. in the monastery, as well as books; translations also from Greek originals, now lost, and from Persian and Syriac, etc.; besides works of their own people. Four years ago the French instituted an Armenian professorship. Twenty pupils presented themselves on Monday morning, full of noble ardour, ingenuous youth, and impregnable industry. They persevered, with a courage worthy of the nation and of universal conquest, till Thursday; when fifteen of the twenty succumbed to the six-and-twentieth letter of the alphabet. It is, to be sure, a Waterloo of an Alphabet—that must be said for them.—Lord Byron, Letter to Thomas Moore

Looking Backward

A poet in our times is a semi-barbarian in a civilized community. He lives in the days that are past. His ideas, thoughts, feelings, associations, are all with barbarous manners, obsolete customs, and exploded superstitions. The march of his intellect is like that of a crab, backward. The brighter the light diffused around him by the progress of reason, the thicker is the darkness of antiquated barbarism, in which he buries himself like a mole, to throw up the barren hillocks of his Cimmerian labours.—Thomas Love Peacock, “The Four Ages of Poetry,” Works Vol. III

Text: Still a Good Book

Textual problems have led some modern scholars to question the credibility of the Gospels and even to doubt the historical existence of Christ. These studies have provoked an intriguing reaction from an unlikely source: Julien Gracq—an old and prestigious novelist, who was close to the Surrealist movement—made a comment which is all the more arresting for coming from an agnostic. In a recent volume of essays, Gracq first acknowledged the impressive learning of one of these scholars (whose lectures he had attended in his youth), as well as the devastating logic of his reasoning; but he confessed that, in the end, he still found himself left with one fundamental objection: for all his formidable erudition, the scholar in question had simply no ear—he could not hear what should be so obvious to any sensitive reader—that, underlying the text of the Gospels, there is a masterly and powerful unity of style, which derives from one unique and inimitable voice; there is the presence of one singular and exceptional personality whose expression is so original, so bold that one could positively call it impudent. Now, if you deny the existence of Jesus, you must transfer all these attributes to some obscure, anonymous writer, who should have had the improbable genius of inventing such a character—or, even more implausibly, you must transfer this prodigious capacity for invention to an entire committee of writers. And Gracq concluded: in the end, if modern scholars, progressive-minded clerics and the docile public all surrender to this critical erosion of the Scriptures, the last group of defenders who will obstinately maintain that there is a living Jesus at the central core of the Gospels will be made of artists and creative writers, for whom the psychological evidence of style carries much more weight than mere philological arguments.—Simon Leys, The Hall of Uselessness: Collected Essays

Horace Odes 1.11 in Three Languages

ENGLISH (Literal Translation)

Don’t ask—it’s forbidden to know—what final fate the gods have given to me and you, Leuconoe, and don’t consult Babylonian horoscopes. How much better it is to accept whatever shall be, whether Jupiter has given many more winters or whether this is the last one, which now breaks the force of the Tuscan sea against the facing cliffs. Be wise, strain the wine, and trim distant hope within short limits. While we’re talking, grudging time will already have fled: seize the day, trusting as little as possible in tomorrow.

LATIN (Original)

Tu ne quaesieris, scire nefas, quem mihi, quem tibi

finem di dederint, Leuconoe, nec Babylonios

temptaris numeros. ut melius, quicquid erit, pati,

seu pluris hiemes seu tribuit Iuppiter ultimam,

quae nunc oppositis debilitat pumicibus mare

Tyrrhenum: sapias, vina liques, et spatio brevi

spem longam reseces. dum loquimur, fugerit invida

aetas: carpe diem, quam minimum credula postero.

SCOTTISH DIALECT (With Glossary)

Ne’er fash your thumb what gods decree

To be the weird o’ you or me,

Nor deal in cantrip’s kittle cunning

To speir how fast your days are running;

But patient lippen for the best,

Nor be in dowie thought opprest.

Whether we see mair winter’s come,

Than this that spits wi’ canker’d foam.

Now moisten weel your geyzen’d wa’s

Wi’ couthy friends and hearty blaws;

Ne’er let your hope o’ergang your days,

For eild and thraldom never stays;

The day looks gash, toot aff your horn,

Nor care ae strae about the morn.

ae: one, a single

blaws: blows (back-slappings?)

canker’d: gusty, stormy

cantrip: magic

couthy: agreeable, sociable

dowie: sad, melancholy

eild: age, time of life

fash: trouble, bother, fret (fash your thumb = care a rap)

gash: pale, dismal

geyzen’d: dried out

kittle: tricky

lippen: trust, have confidence

morn: tomorrow

speir: ask

strae: straw

wa’s: ? The context requires something like weasand (Scots weason) = throat, but the only definitions I can find for wa’s are walls and ways, from which I can extract no satisfactory sense. Or could it be waes = woes?

weird: fate, destiny

“No More Than Weeds or Chaff”

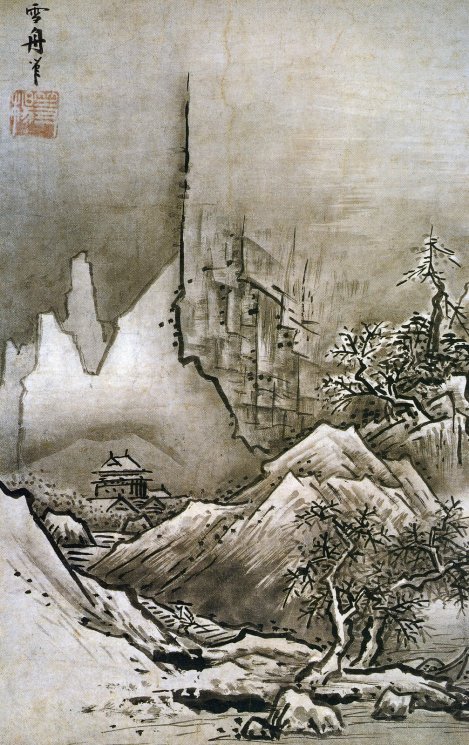

Years ago, at the opening of Dartmouth College’s Hopkins Center, I saw an exhibit of Sesshu Toyo’s Long Scroll and fell in love with it and with the Chinese landscape artists it was imitating. That was the beginning of my fascination with old Chinese landscapes and poetry.

The following lines by Fu Xuan (A.D. 217-278) are as good as the best:

A gentle wind fans the calm night:

A bright moon shines on the high tower.

A voice whispers, but no one answers when I call:

A shadow stirs, but no one comes when I beckon,

The kitchen-man brings in a dish of lentils:

Wine is there, but I do not fill my cup.

Contentment with poverty is Fortune’s best gift:

Riches and Honour are the handmaids of Disaster.

Though gold and gems by the world are sought and prized,

To me they seem no more than weeds or chaff.

Perhaps this Thanksgiving, we should be like the narrator of this poem. Living in the midst of abundance, perhaps we do not need to fill our glass with wine. As the poet says, “Contentment with poverty is Fortune’s best gift.” There is something to that. Today, and always, enjoy your dish of lentils.

Hire This Man!

‘Suppose I was inclined to take you into my service (said he) what are your qualifications? what are you good for?’ ‘An please your honour (answered this original) I can read and write, and do the business of the stable indifferent well — I can dress a horse, and shoe him, and bleed and rowel him; and, as for the practice of sow-gelding, I won’t turn my back on e’er a he in the county of Wilts — Then I can make hog’s puddings and hob-nails, mend kettles and tin sauce-pans.’ — Here uncle burst out a-laughing; and inquired what other accomplishments he was master of — ‘I know something of single-stick, and psalmody (proceeded Clinker); I can play upon the Jew’s-harp, sing Black-ey’d Susan, Arthur-o’Bradley, and divers other songs; I can dance a Welsh jig, and Nancy Dawson; wrestle a fall with any lad of my inches, when I’m in heart; and, under correction, I can find a hare when your honour wants a bit of game.’—Tobias Smollett, The Expedition of Humphry Clinker

You must be logged in to post a comment.